Province of Canada

Province in CanadaBritish Columbia

Motto(s): Splendor Sine Occasu (Latin)(“Splendour without diminishment”)

Coordinates: 54°N 125°W / 54°N 125°W / 54; -125[4]Coordinates: 54°N 125°W / 54°N 125°W / 54; -125[4]CountryCanadaConfederationJuly 20, 1871 (6th)CapitalVictoriaLargest cityVancouver Largest metroGreater Vancouver

• TypeParliamentary constitutional monarchy • Lieutenant governorJanet Austin • PremierDavid Eby LegislatureLegislative Assembly of British ColumbiaFederal representationParliament of CanadaHouse seats42 of 338 (12.4%)Senate seats6 of 105 (5.7%)

• Total944,735 km2 (364,764 sq mi) • Land925,186 km2 (357,216 sq mi) • Water19,548.9 km2 (7,547.9 sq mi) 2.1% • Rank5th 9.5% of Canada • Total5,000,879 [5] • Estimate (Q3 2022)5,319,324 [6] • Rank3rd • Density5.41/km2 (14.0/sq mi)DemonymBritish Columbian[a] Official languagesEnglish (de facto)

• Rank4th • Total (2015)CA$249.981 billion[7] • Per capitaCA$53,267 (8th) • HDI (2019)0.938[8] — Very high (2nd)Most of province[b]UTC−08:00 (Pacific) • Summer (DST)UTC−07:00 (Pacific DST)SoutheasternUTC−07:00 (Mountain) • Summer (DST)UTC−06:00 (Mountain DST)EasternUTC−07:00 (Mountain [no DST])Canadian postal abbr.BCPostal code prefixISO 3166 codeCA-BCFlowerPacific dogwoodTreeWestern red cedarBirdSteller’s jayRankings include all provinces and territories

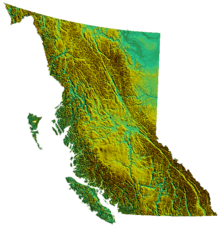

British Columbia (commonly abbreviated as BC) is the westernmost province of Canada, situated between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains. It has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that include rocky coastlines, sandy beaches, forests, lakes, mountains, inland deserts and grassy plains,[9] and borders the province of Alberta to the east and the Yukon and Northwest Territories to the north. With an estimated population of 5.3 million as of 2022, it is Canada’s third-most populous province.[10] The capital of British Columbia is Victoria and its largest city is Vancouver. Vancouver is the third-largest metropolitan area in Canada; the 2021 census recorded 2.6 million people in Metro Vancouver.[11]

The first known human inhabitants of the area settled in British Columbia at least 10,000 years ago. Such groups include the Coast Salish, Tsilhqotʼin, and Haida peoples, among many others. One of the earliest British settlements in the area was Fort Victoria, established in 1843, which gave rise to the city of Victoria, the capital of the Colony of Vancouver Island. The Colony of British Columbia (1858–1866) was subsequently founded by Richard Clement Moody,[12] and by the Royal Engineers, Columbia Detachment, in response to the Fraser Canyon Gold Rush. Moody selected the site for and founded the mainland colony’s capital New Westminster.[13][14][15] The colonies of Vancouver Island and British Columbia were incorporated in 1866, subsequent to which Victoria became the united colony’s capital. In 1871, British Columbia entered Confederation as the sixth province of Canada, in enactment of the British Columbia Terms of Union.

British Columbia is a diverse and cosmopolitan province, drawing on a plethora of cultural influences from its British Canadian, European, and Asian diasporas, as well as the Indigenous population. Though the province’s ethnic majority originates from the British Isles, many British Columbians also trace their ancestors to continental Europe, East Asia, and South Asia.[16] Indigenous Canadians constitute about 6 percent of the province’s total population.[17] Christianity is the largest religion in the region.[18] English is the common language of the province, although Punjabi, Mandarin Chinese, and Cantonese also have a large presence in the Metro Vancouver region. The Franco-Columbian community is an officially recognized linguistic minority, and around one percent of British Columbians claim French as their mother tongue.[19] British Columbia is home to at least 34 distinct Indigenous languages.[20]

Major sectors of British Columbia’s economy include forestry, mining, filmmaking and video production, tourism, real estate, construction, wholesale, and retail. Its main exports include lumber and timber, pulp and paper products, copper, coal, and natural gas.[21] British Columbia exhibits high property values and is a significant centre for maritime trade:[22] the Port of Vancouver is the largest port in Canada and the most diversified port in North America.[23] Although less than 5 percent of the province’s territory is arable land, significant agriculture exists in the Fraser Valley and Okanagan due to the warmer climate.[24] British Columbia is home to 45% of all publicly listed companies in Canada.[25]

Etymology[edit]

The province’s name was chosen by Queen Victoria, when the Colony of British Columbia (1858–1866), i.e., “the Mainland”, became a British colony in 1858.[26] It refers to the Columbia District, the British name for the territory drained by the Columbia River, in southeastern British Columbia, which was the namesake of the pre-Oregon Treaty Columbia Department of the Hudson’s Bay Company. Queen Victoria chose British Columbia to distinguish what was the British sector of the Columbia District from the United States (“American Columbia” or “Southern Columbia”), which became the Oregon Territory on August 8, 1848, as a result of the treaty.[27]

Ultimately, the Columbia in the name British Columbia is derived from the name of the Columbia Rediviva, an American ship which lent its name to the Columbia River and later the wider region;[28] the Columbia in the name Columbia Rediviva came from the name Columbia for the New World or parts thereof, a reference to Christopher Columbus.

The governments of Canada and British Columbia recognize Colombie-Britannique as the French name for the province.[29][30] However, as of 2016, French language is spoken by a small minority of BC residents (1.4%)[31] and is not recognized as official on the provincial level.

Geography[edit]

British Columbia’s geography is epitomized by the variety and intensity of its physical relief, which has defined patterns of settlement and industry since colonization.

British Columbia is bordered to the west by the Pacific Ocean and the American state of Alaska, to the north by Yukon and the Northwest Territories, to the east by the province of Alberta, and to the south by the American states of Washington, Idaho, and Montana. The southern border of British Columbia was established by the 1846 Oregon Treaty, although its history is tied with lands as far south as California. British Columbia’s land area is 944,735 square kilometres (364,800 sq mi). British Columbia’s rugged coastline stretches for more than 27,000 kilometres (17,000 mi), and includes deep, mountainous fjords and about 6,000 islands, most of which are uninhabited. It is the only province in Canada that borders the Pacific Ocean.

British Columbia’s capital is Victoria, located at the southeastern tip of Vancouver Island. Only a narrow strip of Vancouver Island, from Campbell River to Victoria, is significantly populated. Much of the western part of Vancouver Island and the rest of the coast is covered by temperate rainforest.

The province’s most populous city is Vancouver, which is at the confluence of the Fraser River and Georgia Strait, in the mainland’s southwest corner (an area often called the Lower Mainland). By land area, Abbotsford is the largest city. Vanderhoof is near the geographic centre of the province.[32]

Outline map of British Columbia with significant cities and towns

The Coast Mountains and the Inside Passage’s many inlets provide some of British Columbia’s renowned and spectacular scenery, which forms the backdrop and context for a growing outdoor adventure and ecotourism industry. 75 percent of the province is mountainous (more than 1,000 metres (3,300 ft) above sea level); 60 percent is forested; and only about 5 percent is arable.

The province’s mainland away from the coastal regions is somewhat moderated by the Pacific Ocean. Terrain ranges from dry inland forests and semi-arid valleys, to the range and canyon districts of the Central and Southern Interior, to boreal forest and subarctic prairie in the Northern Interior. High mountain regions both north and south have subalpine flora[33] and subalpine climate.

The Okanagan wine area, extending from Vernon to Osoyoos at the United States border, is one of several wine and cider-producing regions in Canada. Other wine regions in British Columbia include the Cowichan Valley on Vancouver Island and the Fraser Valley.

The Southern Interior cities of Kamloops and Penticton have some of the warmest and longest summer climates in Canada (while higher elevations are cold and snowy), although their temperatures are often exceeded north of the Fraser Canyon, close to the confluence of the Fraser and Thompson rivers, where the terrain is rugged and covered with desert-type flora. Semi-desert grassland is found in large areas of the Interior Plateau, with land uses ranging from ranching at lower altitudes to forestry at higher ones.

The northern, mostly mountainous, two-thirds of the province is largely unpopulated and undeveloped, except for the area east of the Rockies, where the Peace River Country contains BC’s portion of the Canadian Prairies, centred at the city of Dawson Creek.

British Columbia is considered part of the Pacific Northwest and the Cascadia bioregion, along with the American states of Alaska, Idaho, (western) Montana, Oregon, Washington, and (northern) California.[34][35]

Climate[edit]

Because of the many mountain ranges and rugged coastline, British Columbia’s climate varies dramatically across the province.

Coastal southern British Columbia has a mild, rainy oceanic climate, influenced by the North Pacific Current, which has its origins in the Kuroshio Current. Hucuktlis Lake on Vancouver Island receives an average of 6,903 mm (271.8 in) of rain annually, and some parts of the area are even classified as warm-summer Mediterranean, the northernmost occurrence in the world. In Victoria, the annual average temperature is 11.2 °C (52.2 °F), the warmest in Canada.

Due to the blocking presence of successive mountain ranges, the climate of some of the interior valleys of the province is semi-arid with certain locations receiving less than 250 millimetres (10 in) in annual precipitation. The annual mean temperature in the most populated areas of the province is up to 12 °C (54 °F), the mildest anywhere in Canada.

The valleys of the Southern Interior have short winters with only brief bouts of cold or infrequent heavy snow, while those in the Cariboo, in the Central Interior, are colder because of increased altitude and latitude, but without the intensity or duration experienced at similar latitudes elsewhere in Canada. For example, the average daily low in Prince George (roughly in the middle of the province) in January is −12 °C (10 °F).[36] Small towns in the southern interior with high elevation such as Princeton are typically colder and snowier than cities in the valleys.[37]

Heavy snowfall occurs in all elevated mountainous terrain providing bases for skiers in both south and central British Columbia. Annual snowfall on highway mountain passes in the southern interior rivals some of the snowiest cities in Canada,[38] and freezing rain and fog are sometimes present on such roads as well.[39] This can result in hazardous driving conditions, as people are usually travelling between warmer areas such as Vancouver or Kamloops, and may be unaware that the conditions may be slippery and cold.[40]

Shuswap Lake as seen from Sorrento

Winters are generally severe in the Northern Interior, but even there, milder air can penetrate far inland. The coldest temperature in British Columbia was recorded in Smith River, where it dropped to −58.9 °C (−74.0 °F) on January 31, 1947,[41] one of the coldest readings recorded anywhere in North America. Atlin in the province’s far northwest, along with the adjoining Southern Lakes region of Yukon, get midwinter thaws caused by the Chinook effect, which is also common (and much warmer) in more southerly parts of the Interior.

During winter on the coast, rainfall, sometimes relentless heavy rain, dominates because of consistent barrages of cyclonic low-pressure systems from the North Pacific. Average snowfall on the coast during a normal winter is between 25 and 50 centimetres (10 and 20 in), but on occasion (and not every winter) heavy snowfalls with more than 20 centimetres (8 in) and well below freezing temperatures arrive when modified arctic air reaches coastal areas, typically for short periods, and can take temperatures below −10 °C (14 °F), even at sea level. Arctic outflow winds can occasionally result in wind chill temperatures at or even below −17.8 °C (0.0 °F).[citation needed]. While winters are very wet, coastal areas are generally milder and dry during summer under the influence of stable anti-cyclonic high pressure.

Southern Interior valleys are hot in summer; for example, in Osoyoos, the July maximum temperature averages 31.7 °C (89.1 °F), making it the hottest month of any location in Canada; this hot weather sometimes spreads towards the coast or to the far north of the province. Temperatures often exceed 40 °C (104 °F) in the lower elevations of valleys in the Interior during mid-summer, with the record high of 49.6 °C (121.3 °F) being held in Lytton on June 29, 2021, during a record-breaking heat wave that year.[42]

The Okanagan region has a climate suitable to vineyards.

The extended summer dryness often creates conditions that spark forest fires, from dry-lightning or man-made causes. Many areas of the province are often covered by a blanket of heavy cloud and low fog during the winter months, in contrast to abundant summer sunshine. Annual sunshine hours vary from 2200 near Cranbrook and Victoria to less than 1300 in Prince Rupert, on the North Coast just south of Southeast Alaska.

The exception to British Columbia’s wet and cloudy winters is during the El Niño phase. During El Niño events, the jet stream is much farther south across North America, making the province’s winters milder and drier than normal. Winters are much wetter and cooler during the opposite phase, La Niña.

Average daily maximum and minimum temperatures for selected cities in British Columbia[43]

Municipality

January

April

July

October

Max

Min

Max

Min

Max

Min

Max

Min

Prince Rupert

5.6 °C (42.1 °F)

−0.8 °C (30.6 °F)

10.2 °C (50.4 °F)

2.5 °C (36.5 °F)

16.2 °C (61.2 °F)

10.5 °C (50.9 °F)

11.1 °C (52.0 °F)

4.9 °C (40.8 °F)

Tofino

8.3 °C (46.9 °F)

2.3 °C (36.1 °F)

11.9 °C (53.4 °F)

4.0 °C (39.2 °F)

18.9 °C (66.0 °F)

10.5 °C (50.9 °F)

13.6 °C (56.5 °F)

6.3 °C (43.3 °F)

Nanaimo

6.9 °C (44.4 °F)

0.1 °C (32.2 °F)

14.1 °C (57.4 °F)

3.9 °C (39.0 °F)

23.9 °C (75.0 °F)

12.3 °C (54.1 °F)

14.6 °C (58.3 °F)

5.2 °C (41.4 °F)

Victoria

7.6 °C (45.7 °F)

1.5 °C (34.7 °F)

13.6 °C (56.5 °F)

4.3 °C (39.7 °F)

22.4 °C (72.3 °F)

11.3 °C (52.3 °F)

14.2 °C (57.6 °F)

5.7 °C (42.3 °F)

Vancouver

6.9 °C (44.4 °F)

1.4 °C (34.5 °F)

13.2 °C (55.8 °F)

5.6 °C (42.1 °F)

22.2 °C (72.0 °F)

13.7 °C (56.7 °F)

13.5 °C (56.3 °F)

7.0 °C (44.6 °F)

Chilliwack

6.1 °C (43.0 °F)

0.4 °C (32.7 °F)

15.8 °C (60.4 °F)

5.2 °C (41.4 °F)

25.0 °C (77.0 °F)

12.5 °C (54.5 °F)

15.3 °C (59.5 °F)

6.4 °C (43.5 °F)

Penticton

1.8 °C (35.2 °F)

−3.0 °C (26.6 °F)

15.7 °C (60.3 °F)

2.5 °C (36.5 °F)

28.7 °C (83.7 °F)

13.3 °C (55.9 °F)

14.3 °C (57.7 °F)

3.2 °C (37.8 °F)

Kamloops

0.4 °C (32.7 °F)

−5.9 °C (21.4 °F)

16.6 °C (61.9 °F)

3.2 °C (37.8 °F)

28.9 °C (84.0 °F)

14.2 °C (57.6 °F)

13.7 °C (56.7 °F)

3.3 °C (37.9 °F)

Osoyoos

2.0 °C (35.6 °F)

−3.8 °C (25.2 °F)

18.1 °C (64.6 °F)

3.6 °C (38.5 °F)

31.5 °C (88.7 °F)

14.3 °C (57.7 °F)

16.4 °C (61.5 °F)

3.5 °C (38.3 °F)

Princeton

−1.4 °C (29.5 °F)

−8.6 °C (16.5 °F)

14.4 °C (57.9 °F)

−0.3 °C (31.5 °F)

26.3 °C (79.3 °F)

9.5 °C (49.1 °F)

13.2 °C (55.8 °F)

0.3 °C (32.5 °F)

Cranbrook

−1.9 °C (28.6 °F)

−10.2 °C (13.6 °F)

12.9 °C (55.2 °F)

0.3 °C (32.5 °F)

26.2 °C (79.2 °F)

11.2 °C (52.2 °F)

11.7 °C (53.1 °F)

−0.3 °C (31.5 °F)

Prince George

−4.0 °C (24.8 °F)

−11.7 °C (10.9 °F)

11.2 °C (52.2 °F)

−1.1 °C (30.0 °F)

22.4 °C (72.3 °F)

9.1 °C (48.4 °F)

9.4 °C (48.9 °F)

−0.5 °C (31.1 °F)

Fort Nelson

−16.1 °C (3.0 °F)

−24.6 °C (−12.3 °F)

9.6 °C (49.3 °F)

−3.6 °C (25.5 °F)

23.2 °C (73.8 °F)

10.9 °C (51.6 °F)

5.2 °C (41.4 °F)

−4.2 °C (24.4 °F)

Parks and protected areas[edit]

There are 14 designations of parks and protected areas in the province that reflect the different administration and creation of these areas in a modern context. There are 141 ecological reserves, 35 provincial marine parks, 7 provincial heritage sites, 6 National Historic Sites of Canada, 4 national parks and 3 national park reserves. 12.5 percent of the province’s area (114,000 km2 or 44,000 sq mi) is considered protected under one of the 14 different designations that includes over 800 distinct areas.

British Columbia contains seven of Canada’s national parks and National Park Reserves:

British Columbia contains a large number of provincial parks, run by BC Parks under the aegis of the Ministry of Environment. British Columbia’s provincial parks system is the second largest parks system in Canada, the largest being Canada’s National Parks system.

Another tier of parks in British Columbia are regional parks, which are maintained and run by the province’s regional districts. The Ministry of Forests operates forest recreation sites.

In addition to these areas, over 47,000 square kilometres (18,000 sq mi) of arable land are protected by the Agricultural Land Reserve.

Fauna[edit]

Much of the province is undeveloped, so populations of many mammalian species that have become rare in much of the United States still flourish in British Columbia.[44] Watching animals of various sorts, including a very wide range of birds, has long been popular. Bears (grizzly, black—including the Kermode bear or spirit bear) live here, as do deer, elk, moose, caribou, big-horn sheep, mountain goats, marmots, beavers, muskrats, coyotes, wolves, mustelids (such as wolverines, badgers and fishers), cougars, eagles, ospreys, herons, Canada geese, swans, loons, hawks, owls, ravens, harlequin ducks, and many other sorts of ducks. Smaller birds (robins, jays, grosbeaks, chickadees, and so on) also abound.[45] Murrelets are known from Frederick Island, a small island off the coast of Haida Gwaii.[46]

Many healthy populations of fish are present, including salmonids such as several species of salmon, trout, char. Besides salmon and trout, sport-fishers in BC also catch halibut, steelhead, bass, and sturgeon. On the coast, harbour seals and river otters are common.[47] Cetacean species native to the coast include the orca, humpback whale, grey whale, harbour porpoise, Dall’s porpoise, Pacific white-sided dolphin and minke whale.

Some endangered species in British Columbia are: Vancouver Island marmot, spotted owl, American white pelican, and badgers.

Endangered species in British Columbia[48]

Type of organism

Red-listed species in BC

Total number of species in BC

Freshwater fish

24

80

Amphibians

5

19

Reptiles

6

16

Birds

34

465

Terrestrial mammals

(Requires new data)

(Requires new data)

Marine mammals

3

29

Plants

257

2333

Butterflies

19

187

Dragonflies

9

87

Forests[edit]

White spruce or Engelmann spruce and their hybrids occur in 12 of the 14 biogeoclimatic zones of British Columbia.[49] Common types of trees present in BC’s forests include western redcedar, yellow-cedar, Rocky Mountain juniper, lodgepole pine, ponderosa or yellow pine, whitebark pine, limber pine, western white pine, western larch, tamarack, alpine larch, white spruce, Engelmann spruce, Sitka spruce, black spruce, grand fir, Amabilis fir, subalpine fir, western hemlock, mountain hemlock, Douglas-fir, western yew, Pacific dogwood, bigleaf maple, Douglas maple, vine maple, arbutus, black hawthorn, cascara, Garry oak, Pacific crab apple, choke cherry, pin cherry, bitter cherry, red alder, mountain alder, paper birch, water birch, black cottonwood, balsam poplar, trembling aspen.

Traditional plant foods[edit]

First Nations peoples of British Columbia used plants for food, and to produce material goods like fuel and building products. Plant foods included berries, and roots like camas.[50]

Ecozones[edit]

Environment Canada subdivides British Columbia into six ecozones:

History[edit]

Indigenous societies[edit]

‘Namgis Thunderbird Transformation Mask, 19th century

The area now known as British Columbia is home to First Nations groups that have a deep history with a significant number of indigenous languages. There are more than 200 First Nations in BC. Prior to contact (with non-Aboriginal people), human history is known from oral histories of First Nations groups, archaeological investigations, and from early records from explorers encountering societies early in the period.

The arrival of Paleoindians from Beringia took place between 20,000 and 12,000 years ago.[51] Hunter-gatherer families were the main social structure from 10,000 to 5,000 years ago.[52] The nomadic population lived in non-permanent structures foraging for nuts, berries and edible roots while hunting and trapping larger and small game for food and furs.[52] Around 5,000 years ago individual groups started to focus on resources available to them locally. Coast Salish peoples’ had complex land management practices linked to ecosystem health and resilience. Forest gardens on Canada’s northwest coast included crabapple, hazelnut, cranberry, wild plum, and wild cherry species.[53] Thus with the passage of time there is a pattern of increasing regional generalization with a more sedentary lifestyle.[52] These indigenous populations evolved over the next 5,000 years across a large area into many groups with shared traditions and customs.

To the northwest of the province are the peoples of the Na-Dene languages, which include the Athapaskan-speaking peoples and the Tlingit, who lived on the islands of southern Alaska and northern British Columbia. The Na-Dene language group is believed to be linked to the Yeniseian languages of Siberia.[54] The Dene of the western Arctic may represent a distinct wave of migration from Asia to North America.[54] The Interior of British Columbia was home to the Salishan language groups such as the Shuswap (Secwepemc), Okanagan and Athabaskan language groups, primarily the Dakelh (Carrier) and the Tsilhqot’in.[55] The inlets and valleys of the British Columbia coast sheltered large, distinctive populations, such as the Haida, Kwakwaka’wakw and Nuu-chah-nulth, sustained by the region’s abundant salmon and shellfish.[55] These peoples developed complex cultures dependent on the western red cedar that included wooden houses, seagoing whaling and war canoes and elaborately carved potlatch items and totem poles.[55]

Contact with Europeans brought a series of devastating epidemics of diseases from Europe the people had no immunity to.[56] The result was a dramatic population collapse, culminating in the 1862 Smallpox outbreak in Victoria that spread throughout the coast. European settlement did not bode well for the remaining native population of British Columbia. Colonial officials deemed colonists could make better use of the land than the First Nations people, and thus the land territory be owned by the colonists.[57]: 120 To ensure colonists would be able to settle properly and make use of the land, First Nations were forcibly relocated onto reserves, which were often too small to support their way of life.[57]: 120–121 By the 1930s, British Columbia had over 1500 reserves.[57]: 121

Fur trade and colonial era[edit]

Lands now known as British Columbia were added to the British Empire during the 19th century. Colonies originally begun with the support of the Hudson’s Bay Company (Vancouver Island, the mainland) were amalgamated, then entered Confederation as British Columbia in 1871 as part of the Dominion of Canada.

During the 1770s, smallpox killed at least 30 percent of the Pacific Northwest First Nations.[58] This devastating epidemic was the first in a series; the 1862 Pacific Northwest smallpox epidemic killed about half to two-thirds of the native population of what became British Columbia.[59][60][61]

The arrival of Europeans began around the mid-18th century, as fur traders entered the area to harvest sea otters. While it is thought Sir Francis Drake may have explored the British Columbian coast in 1579, it was Juan Pérez who completed the first documented voyage, which took place in 1774. Juan Francisco de la Bodega y Quadra explored the coast in 1775. In doing so, Pérez and Quadra reasserted the Spanish claim for the Pacific coast, first made by Vasco Núñez de Balboa in 1513.

The explorations of James Cook in 1778 and George Vancouver in 1792 and 1793 established British jurisdiction over the coastal area north and west of the Columbia River. In 1793, Sir Alexander Mackenzie was the first European to journey across North America overland to the Pacific Ocean, inscribing a stone marking his accomplishment on the shoreline of Dean Channel near Bella Coola. His expedition theoretically established British sovereignty inland, and a succession of other fur company explorers charted the maze of rivers and mountain ranges between the Canadian Prairies and the Pacific. Mackenzie and other explorers—notably John Finlay, Simon Fraser, Samuel Black, and David Thompson—were primarily concerned with extending the fur trade, rather than political considerations. In 1794, by the third of a series of agreements known as the Nootka Conventions, Spain conceded its claims of exclusivity in the Pacific. This opened the way for formal claims and colonization by other powers, including Britain, but because of the Napoleonic Wars, there was little British action on its claims in the region until later.

The establishment of trading posts by the North West Company and the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC), effectively established a permanent British presence in the region. The Columbia District was broadly defined as being south of 54°40 north latitude, (the southern limit of Russian America), north of Mexican-controlled California, and west of the Rocky Mountains. It was, by the Anglo-American Convention of 1818, under the “joint occupancy and use” of citizens of the United States and subjects of Britain (which is to say, the fur companies). This co-occupancy was ended with the Oregon Treaty of 1846.

The major supply route was the York Factory Express between Hudson Bay and Fort Vancouver. Some of the early outposts grew into settlements, communities, and cities. Among the places in British Columbia that began as fur trading posts are Fort St. John (established 1794); Hudson’s Hope (1805); Fort Nelson (1805); Fort St. James (1806); Prince George (1807); Kamloops (1812); Fort Langley (1827); Fort Victoria (1843); Yale (1848); and Nanaimo (1853). Fur company posts that became cities in what is now the United States include Vancouver, Washington (Fort Vancouver), formerly the “capital” of Hudson’s Bay operations in the Columbia District, Colville, Washington and Walla Walla, Washington (old Fort Nez Percés).

With the amalgamation of the two fur trading companies in 1821, modern-day British Columbia existed in three fur trading departments. The bulk of the central and northern interior was organized into the New Caledonia district, administered from Fort St. James. The interior south of the Thompson River watershed and north of the Columbia was organized into the Columbia District, administered from Fort Vancouver on the lower Columbia River. The northeast corner of the province east of the Rockies, known as the Peace River Block, was attached to the much larger Athabasca District, headquartered in Fort Chipewyan, in present-day Alberta.

Until 1849, these districts were a wholly unorganized area of British North America under the de facto jurisdiction of HBC administrators; however, unlike Rupert’s Land to the north and east, the territory was not a concession to the company. Rather, it was simply granted a monopoly to trade with the First Nations inhabitants. All that was changed with the westward extension of American exploration and the concomitant overlapping claims of territorial sovereignty, especially in the southern Columbia Basin (within present day Washington and Oregon). In 1846, the Oregon Treaty divided the territory along the 49th parallel to the Strait of Georgia, with the area south of this boundary (excluding Vancouver Island and the Gulf Islands) transferred to sole American sovereignty. The Colony of Vancouver Island was created in 1849, with Victoria designated as the capital. New Caledonia, as the whole of the mainland rather than just its north-central Interior came to be called, continued to be an unorganized territory of British North America, “administered” by individual HBC trading post managers.

Colony of British Columbia (1858–1866)[edit]

With the Fraser Canyon Gold Rush in 1858, an influx of Americans into New Caledonia prompted the colonial office to designate the mainland as the Colony of British Columbia. When news of the Fraser Canyon Gold Rush reached London, Richard Clement Moody was hand-picked by the Colonial Office, under Sir Edward Bulwer-Lytton, to establish British order and to transform the newly established Colony of British Columbia into the British Empire’s “bulwark in the farthest west”[62] and “found a second England on the shores of the Pacific”. Lytton desired to send to the colony “representatives of the best of British culture, not just a police force”: he sought men who possessed “courtesy, high breeding and urbane knowledge of the world”[64]: 13 and he decided to send Moody, whom the Government considered to be the “English gentleman and British Officer”[64]: 19 at the head of the Royal Engineers, Columbia Detachment.

Moody and his family arrived in British Columbia in December 1858, commanding the Royal Engineers, Columbia Detachment.[12] He was sworn in as the first lieutenant governor of British Columbia and appointed Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works for British Columbia. On the advice of Lytton, Moody hired Robert Burnaby as his personal secretary.

Cattle near the Maas by Dutch painter Aelbert Cuyp. Moody likened his vision of the nascent Colony of British Columbia to the pastoral scenes painted by Cuyp.

In British Columbia, Moody “wanted to build a city of beauty in the wilderness” and planned his city as an iconic visual metaphor for British dominance, “styled and located with the objective of reinforcing the authority of the crown and of the robe”.[64]: 26 Subsequent to the enactment of the Pre-emption Act of 1860, Moody settled the Lower Mainland. He selected the site and founded the new capital, New Westminster. He selected the site due to the strategic excellence of its position and the quality of its port.[64]: 26 He was also struck by the majestic beauty of the site, writing in his letter to Blackwood,

The entrance to the Frazer is very striking—Extending miles to the right & left are low marsh lands (apparently of very rich qualities) & yet fr the Background of Superb Mountains– Swiss in outline, dark in woods, grandly towering into the clouds there is a sublimity that deeply impresses you. Everything is large and magnificent, worthy of the entrance to the Queen of England’s dominions on the Pacific mainland. … My imagination converted the silent marshes into Cuyp-like pictures of horses and cattle lazily fattening in rich meadows in a glowing sunset. … The water of the deep clear Frazer was of a glassy stillness, not a ripple before us, except when a fish rose to the surface or broods of wild ducks fluttered away.[65]

Lord Lytton “forgot the practicalities of paying for clearing and developing the site and the town” and the efforts of Moody’s engineers were continuously hampered by insufficient funds, which, together with the continuous opposition of Governor James Douglas, “made it impossible for Moody’s design to be fulfilled”.[67][68][64]: 27

Moody and the Royal Engineers also built an extensive road network, including what would become Kingsway, connecting New Westminster to False Creek, the North Road between Port Moody and New Westminster, and the Cariboo Road and Stanley Park.[69] He named Burnaby Lake after his private secretary Robert Burnaby and named Port Coquitlam’s 400-foot “Mary Hill” after his wife. As part of the surveying effort, several tracts were designated “government reserves”, which included Stanley Park as a military reserve (a strategic location in case of an American invasion). The Pre-emption Act did not specify conditions for distributing the land, so large parcels were snapped up by speculators, including 1,518 hectares (3,750 acres) by Moody himself. For this he was criticized by local newspapermen for land grabbing. Moody designed the first coat of arms of British Columbia. Port Moody is named after him. It was established at the end of a trail that connected New Westminster with Burrard Inlet to defend New Westminster from potential attack from the US.

By 1862, the Cariboo Gold Rush, attracting an additional 5000 miners, was underway, and Douglas hastened construction of the Great North Road (commonly known now as the Cariboo Wagon Road) up the Fraser Canyon to the prospecting region around Barkerville. By the time of this gold rush, the character of the colony was changing, as a more stable population of British colonists settled in the region, establishing businesses, opening sawmills, and engaging in fishing and agriculture. With this increased stability, objections to the colony’s absentee governor and the lack of responsible government began to be vocalized, led by the influential editor of the New Westminster British Columbian and future premier, John Robson. A series of petitions requesting an assembly were ignored by Douglas and the colonial office until Douglas was eased out of office in 1864. Finally, the colony would have both an assembly and a resident governor.

Later gold rushes[edit]

A series of gold rushes in various parts of the province followed, the largest being the Cariboo Gold Rush in 1862, forcing the colonial administration into deeper debt as it struggled to meet the extensive infrastructure needs of far-flung boom communities like Barkerville and Lillooet, which sprang up overnight. The Vancouver Island colony was facing financial crises of its own, and pressure to merge the two eventually succeeded in 1866, when the colony of British Columbia was amalgamated with the Colony of Vancouver Island to form the Colony of British Columbia (1866–1871), which was, in turn, succeeded by the present day province of British Columbia following the Canadian Confederation of 1871.

Rapid growth and development[edit]

The Confederation League, including such figures as Amor De Cosmos, John Robson, and Robert Beaven, led the chorus pressing for the colony to join Canada, which had been created out of three British North American colonies in 1867 (the Province of Canada, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick). Several factors motivated this agitation, including the fear of annexation to the United States, the overwhelming debt created by rapid population growth, the need for government-funded services to support this population, and the economic depression caused by the end of the gold rush.

Memorial to the “last spike” in Craigellachie

With the agreement by the Canadian government to extend the Canadian Pacific Railway to British Columbia and to assume the colony’s debt, British Columbia became the sixth province to join Confederation on July 20, 1871. The borders of the province were not completely settled. The Treaty of Washington sent the Pig War San Juan Islands Border dispute to arbitration in 1871 and in 1903, the province’s territory shrank again after the Alaska boundary dispute settled the vague boundary of the Alaska Panhandle.

Population in British Columbia continued to expand as the province’s mining, forestry, agriculture, and fishing sectors were developed. Mining activity was particularly notable throughout the Mainland, particularly in the Boundary Country, in the Slocan, in the West Kootenay around Trail, the East Kootenay (the southeast corner of the province), the Fraser Canyon, the Cariboo, the Omineca and the Cassiar, so much so a common epithet for the Mainland, even after provincehood, was “the Gold Colony”.[70] Agriculture attracted settlers to the fertile Fraser Valley, and cattle ranchers and later fruit growers came to the drier grasslands of the Thompson River area, the Cariboo, the Chilcotin, and the Okanagan. Forestry drew workers to the lush temperate rainforests of the coast, which was also the locus of a growing fishery.

The completion of the railway in 1885 was a huge boost to the province’s economy, facilitating the transportation of the region’s considerable resources to the east. The milltown of Granville, known as Gastown, near the mouth of the Burrard Inlet was selected as the terminus of the railway, prompting the incorporation of the city as Vancouver in 1886. The completion of the Port of Vancouver spurred rapid growth, and in less than fifty years the city surpassed Winnipeg, Manitoba, as the largest in Western Canada. The early decades of the province were ones in which issues of land use—specifically, its settlement and development—were paramount. This included expropriation from First Nations people of their land, control over its resources, as well as the ability to trade in some resources (such as fishing).

Establishing a labour force to develop the province was problematic from the start, and British Columbia was the locus of immigration from Europe, China, Japan and India. The influx of a non-European population stimulated resentment from the dominant ethnic groups, resulting in agitation (much of it successful) to restrict the ability of Asian people to immigrate to British Columbia through the imposition of a head tax. This resentment culminated in mob attacks against Chinese and Japanese immigrants in Vancouver in 1887 and 1907. The subsequent Komagata Maru incident in 1914, where hundreds of Indians were denied entry into Vancouver, was also a direct result of the anti-Asian resentment at the time. By 1923, almost all Chinese immigration had been blocked except for merchants, professionals, students and investors.

Meanwhile, the province continued to grow. In 1914, the last spike of a second transcontinental rail line, the Grand Trunk Pacific, linking north-central British Columbia from the Yellowhead Pass through Prince George to Prince Rupert was driven at Fort Fraser. This opened up the North Coast and the Bulkley Valley region to new economic opportunities. What had previously been an almost exclusively fur trade and subsistence economy soon became a locus for forestry, farming, and mining.

In World War I, the province responded strongly to the call to assist the British Empire against its German foes in French and Belgian battlefields. About 55,570 of the 400,000 British Columbian residents, the highest per-capita rate in Canada, responded to the military needs. Horseriders from the province’s Interior region and First Nations soldiers made contributions to Vimy Ridge and other battles. About 6,225 men from the province died in combat.[71]

1920s to 1940s[edit]

When men returned from the First World War, they discovered the recently enfranchised women of the province voted for the prohibition of liquor in an effort to end the social problems associated with the hard-core drinking in the province was until the war. However, with pressure from veterans, prohibition was quickly relaxed so the “soldier and the working man” could enjoy a drink, but widespread unemployment among veterans was hardened by many of the available jobs being taken by European immigrants and disgruntled veterans organized a range of “soldier parties” to represent their interests, variously named Soldier-Farmer, Soldier-Labour, and Farmer-Labour Parties. These formed the basis of the fractured labour-political spectrum that would generate a host of fringe leftist and rightist parties, including those who would eventually form the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation and the early Social Credit splinter groups.

The advent of prohibition in the United States created opportunities, and many found employment or at least profit in cross-border liquor smuggling. By the end of the 1920s, the end of prohibition in the U.S., combined with the onset of the Great Depression, plunged the province into economic destitution during the 1930s. Compounding the already dire local economic situation, tens of thousands of men from colder parts of Canada swarmed into Vancouver, creating huge hobo jungles around False Creek and the Burrard Inlet rail yards, including the old Canadian Pacific Railway mainline right-of-way through the heart of Downtown Vancouver. Increasingly desperate times led to intense political efforts, an occupation of the main Post Office at Granville and Hastings which was violently put down by the police and an effective imposition of martial law on the docks for almost three years due to the Battle of Ballantyne Pier. A Vancouver contingent for the On-to-Ottawa Trek was organized and seized a train, which was loaded with thousands of men bound for the capital but was met by a Gatling gun straddling train tracks at Mission. All the men were arrested and sent to work camps for the duration of the Depression.[72] There were signs of an economic return towards the end of the 1930s, however, the onset of World War II transformed the national economy and ended the Depression.

British Columbia has long taken advantage of its location on the Pacific Ocean to have close relations with East Asia and South Asia. These relations have often caused friction between cultures which has sometimes escalated into racist animosity towards those of Asian descent. This was manifest during the Second World War when many people of Japanese descent were relocated or interned in the Interior region of the province.

Coalition and the post-war boom[edit]

During the Second World War the mainstream BC Liberal and BC Conservative parties united in a formal coalition government under new Liberal leader John Hart, who replaced Duff Pattullo when the latter failed to win a majority in the 1941 election. While the Liberals won the most seats, they actually received fewer votes than the socialist Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF). Pattullo was unwilling to form a coalition with the rival Conservatives led by Royal Maitland and was replaced by Hart, who formed a coalition cabinet made up of five Liberal and three Conservative ministers.[73] The CCF was invited to join the coalition but refused.[73]

The pretext for continuing the coalition after the end of the Second World War was to prevent the CCF, which had won a surprise victory in Saskatchewan in 1944, from ever coming to power in British Columbia. The CCF’s popular vote was high enough in the 1945 election that they were likely to have won three-way contests and could have formed government; however, the coalition prevented that by uniting the anti-socialist vote.[73] In the post-war environment the government initiated a series of infrastructure projects, notably the completion of Highway 97 north of Prince George to the Peace River Block, a section called the John Hart Highway and also public hospital insurance.

In 1947 the reins of the Coalition were taken by Byron Ingemar Johnson. The Conservatives had wanted their new leader Herbert Anscomb to be premier, but the Liberals in the Coalition refused. Johnson led the coalition to the highest percentage of the popular vote in British Columbia history (61 percent) in the 1949 election. This victory was attributable to the popularity of his government’s spending programmes, despite rising criticism of corruption and abuse of power. During his tenure, major infrastructures continued to expand, such as the agreement with Alcan Aluminum to build the town of Kitimat with an aluminum smelter and the large Kemano Hydro Project.[74] Johnson achieved popularity for flood relief efforts during the 1948 flooding of the Fraser Valley, which was a major blow to that region and to the province’s economy.

On February 13, 1950, a Convair B-36B crashed in northern British Columbia after jettisoning a Mark IV atomic bomb. This was the first such nuclear weapon loss in history.[75]

Increasing tension between the Liberal and Conservative coalition partners led the Liberal Party executive to vote to instruct Johnson to terminate the arrangement. Johnson ended the coalition and dropped his Conservative cabinet ministers, including Deputy Premier and Finance minister Herbert Anscomb, precipitating the general election of 1952.[73] A referendum on electoral reform prior to this election had instigated an elimination ballot (similar to a preferential ballot), where voters could select second and third choices. The intent of the ballot, as campaigned for by Liberals and Conservatives, was that their supporters would list the rival party in lieu of the CCF, but this plan backfired when a large group of voters from all major parties, including the CCF, voted for the fringe Social Credit Party, who wound up with the largest number of seats in the House (19), only one seat ahead of the CCF, despite the CCF having 34.3 percent of the vote to Social Credit’s 30.18 percent.

The Social Credit Party, led by rebel former Conservative MLA W. A. C. Bennett, formed a minority government backed by the Liberals and Conservatives (with 6 and 4 seats respectively). Bennett began a series of fiscal reforms, preaching a new variety of populism as well as waxing eloquent on progress and development, laying the ground for a second election in 1953 in which the new Bennett regime secured a majority of seats, with 38 percent of the vote. Secure with that majority, Bennett returned the province to the first-past-the-post system thereafter, which is still in use.

1952–1960s[edit]

With the election of the Social Credit Party, British Columbia embarked on a phase of rapid economic development. Bennett and his party governed the province for the next twenty years, during which time the government initiated an ambitious programme of infrastructure development, fuelled by a sustained economic boom in the forestry, mining, and energy sectors.

During these two decades, the government nationalized British Columbia Electric and the British Columbia Power Company, as well as smaller electric companies, renaming the entity BC Hydro. West Kootenay Power and Light remained independent of BC Hydro, being owned and operated by Cominco, though tied into the regional power grid. By the end of the 1960s, several major dams had been begun or completed in—among others—the Peace, Columbia, and Nechako River watersheds (the Nechako Diversion to Kemano, was to supply power to the Alcan Inc. aluminum smelter at Kitimat, and was not part of the provincial power grid but privately owned). Major transmission deals were concluded, most notably the Columbia River Treaty between Canada and the United States. The province’s economy was also boosted by unprecedented growth in the forest sector, as well as oil and gas development in the province’s northeast.

The 1950s and 1960s were also marked by development in the province’s transportation infrastructure. In 1960, the government established BC Ferries as a crown corporation, to provide a marine extension of the provincial highway system, also supported by federal grants as being part of the Trans-Canada Highway system. That system was improved and expanded through the construction of new highways and bridges, and paving of existing highways and provincial roads.

Vancouver and Victoria became cultural centres as poets, authors, artists, musicians, as well as dancers, actors, and haute cuisine chefs flocked to its scenery and warmer temperatures, with the cultural and entrepreneurial community bolstered by many Draft dodgers from the United States. Tourism also played a role in the economy. The rise of Japan and other Pacific economies was a boost to British Columbia’s economy, primarily because of exports of lumber products and unprocessed coal and trees.[citation needed]

Politically and socially, the 1960s brought a period of significant social ferment. The divide between the political left and right, which had prevailed in the province since the Depression and the rise of the labour movement, sharpened as so-called free enterprise parties coalesced into the de facto coalition represented by Social Credit—in opposition to the social democratic New Democratic Party (NDP), the successor to the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation. As the province’s economy blossomed, so did labour-management tensions. Tensions emerged, also, from the counterculture movement of the late 1960s, of which Vancouver and Nanaimo were centres. The conflict between hippies and Vancouver mayor Tom Campbell was particularly legendary, culminating in the Gastown riots of 1971. By the end of the decade, with social tensions and dissatisfaction with the status quo rising, the Bennett government’s achievements could not stave off its growing unpopularity.

1970s and 1980s[edit]

On August 27, 1969, the Social Credit Party was re-elected in a general election for what would be Bennett’s final term in power. At the start of the 1970s, the economy was quite strong because of rising coal prices and an increase in annual allowable cuts in the forestry sector, but BC Hydro reported its first loss, which was the beginning of the end for Bennett and the Social Credit Party.[76]

The Socreds were forced from power in the August 1972 election, paving the way for a provincial NDP government under Dave Barrett. Under Barrett, the large provincial surplus soon became a deficit,[citation needed] although changes to the accounting system makes it likely some of the deficit was carried over from the previous Social Credit regime and its “two sets of books”, as W. A. C. Bennett had once referred to his system of fiscal management. The brief three-year (“Thousand Days”) period of NDP governance brought several lasting changes to the province, most notably the creation of the Agricultural Land Reserve, intended to protect farmland from redevelopment, and the Insurance Corporation of British Columbia, a crown corporation charged with a monopoly on providing single-payer basic automobile insurance.

Perceptions the government had instituted reforms either too swiftly or that were too far-reaching, coupled with growing labour disruptions led to the ouster of the NDP in the 1975 general election. Social Credit, under W.A.C. Bennett’s son, Bill Bennett, was returned to office. Under the younger Bennett’s government, 85 percent of the province’s land base was transferred from Government Reserve to management by the Ministry of Forests, reporting of deputy ministers was centralized to the Premier’s Office, and NDP-instigated social programs were rolled back, with then-human resources minister infamously demonstrating a golden shovel to highlight his welfare policy, although the new-era Social Credit Party also reinforced and backed certain others instigated by the NDP—notably the creation of the Resort Municipality of Whistler, whose special status including Sunday drinking, then an anomaly in BC.

British Columbia’s pavilion for Expo 86, Vancouver

Also during the “MiniWac” regime (a reference to his father’s acronym, W. A. C.) certain money-losing Crown-owned assets were “privatized” in a mass giveaway of shares in the British Columbia Resources Investment Corporation, “BCRIC”, with the “Brick shares” soon becoming near-worthless. Towards the end of his tenure in power, Bennett oversaw the completion of several megaprojects meant to stimulate the economy and win votes – unlike most right-wing parties, British Columbia’s Social Credit actively practiced government stimulation of the economy. Most notable of these was the winning of a world’s fair for Vancouver, which came in the form of Expo 86, to which was tied the construction of the Coquihalla Highway and Vancouver’s SkyTrain system. The Coquihalla Highway project became the subject of a scandal after revelations the premier’s brother bought large tracts of land needed for the project before it was announced to the public, and also because of graft investigations of the huge cost overruns on the project. Both investigations were derailed in the media by a still further scandal, the Doman Scandal, in which the premier and millionaire backer Herb Doman were investigated for insider-trading and securities fraud. Nonetheless, the Socreds were re-elected in 1979 under Bennett, who led the party until 1986.

As the province entered a sustained recession, Bennett’s popularity and media image were in decline. On April 1, 1983, Premier Bennett overstayed his constitutional limits of power by exceeding the legal tenure of a government, and the lieutenant governor, Henry Pybus Bell-Irving, was forced to call Bennett to Government House to resolve the impasse, and an election was called for April 30, while in the meantime government cheques were covered by special emergency warrants as the Executive Council no longer had signing authority because of the constitutional crisis. Campaigning on a platform of moderation, Bennett won an unexpected majority.

After several weeks of silence in the aftermath, a sitting of the House was finally called and in the speech from the throne, Social Credit instituted a programme of fiscal cutbacks dubbed “restraint”, which had been a buzzword for moderation during the campaign. The programme included cuts to “motherhood” issues of the left, including the human rights branch, the offices of the Ombudsman and Rentalsman, women’s programs, environmental and cultural programs, while still supplying mass capital infusions to corporate British Columbia. This sparked a backlash, with tens of thousands of people in the streets the next day after the budget speech, and through the course of a summer repeated large demonstrations of up to 100,000 people.

This became known as the 1983 Solidarity Crisis, from the name of the Solidarity Coalition, a huge grassroots opposition movement mobilized, consisting of organized labour and community groups, with the British Columbia Federation of Labour forming a separate organization of unions, Operation Solidarity, under the direction of Jack Munro, then-president of the International Woodworkers of America (IWA), the most powerful of the province’s resource unions. Tens of thousands participated in protests and many felt a general strike would be the inevitable result unless the government backed down from its policies they had claimed were only about restraint and not about recrimination against the NDP and the left. Just as a strike at Pacific Press ended, which had limited the political management of the public agenda by the publishers of the province’s major papers, the movement collapsed after an apparent deal was struck by union leader and IWA president, Jack Munro and Premier Bennett.[77]

A tense winter of blockades at various job sites around the province ensued, as among the new laws were those enabling non-union labour to work on large projects and other sensitive labour issues, with companies from Alberta and other provinces brought in to compete with union-scale British Columbia companies. Despite the tension, Bennett’s last few years in power were relatively peaceful as economic and political momentum grew on the megaprojects associated with Expo, and Bennett was to end his career by hosting Prince Charles and Lady Diana on their visit to open Expo 86. His retirement being announced, a Social Credit convention was scheduled for the Whistler Resort, which came down to a three-way shooting match between Bud Smith, the Premier’s right-hand man but an unelected official, Social Credit party grande dame Grace McCarthy, and the charismatic but eccentric Bill Vander Zalm.

Bill Vander Zalm became the new Social Credit leader when Smith threw his support to him rather than see McCarthy win, and led the party to victory in the election later that year. Vander Zalm was later involved in a conflict of interest scandal following the sale of Fantasy Gardens, a Christian and Dutch culture theme park built by the Premier, to Tan Yu, a Filipino Chinese gambling kingpin. There were also concerns over Yu’s application to the government for a bank licence, and lurid stories from flamboyant realtor Faye Leung of a party in the “Howard Hughes Suite” on the top two floors of the Bayshore Inn, where Tan Yu had been staying, with reports of a bag of money in a brown paper bag passed from Yu to Vander Zalm during the goings-on. These scandals forced Vander Zalm’s resignation, and Rita Johnston became premier of the province. Johnston presided over the end of Social Credit power, calling an election which reduced the party’s caucus to only two seats, and the revival of the long-defunct British Columbia Liberal Party as Opposition to the victorious NDP under former Vancouver mayor Mike Harcourt.

In 1988, David Lam was appointed as British Columbia’s twenty-fifth lieutenant governor, and was the province’s first lieutenant governor of Chinese origin.

1990s to present[edit]

Johnston lost the 1991 general election to the NDP, under the leadership of Mike Harcourt, a former mayor of Vancouver. The NDP’s unprecedented creation of new parkland and protected areas was popular and helped boost the province’s growing tourism sector, although the economy continued to struggle against the backdrop of a weak resource economy. Housing starts and an expanded service sector saw growth overall through the decade, despite political turmoil. Harcourt ended up resigning over “Bingogate”—a political scandal involving the funnelling of charity bingo receipts into party coffers in certain ridings. Harcourt was not implicated, but he resigned nonetheless in respect of constitutional conventions calling for leaders under suspicion to step aside. Glen Clark, a former president of the BC Federation of Labour, was chosen the new leader of the NDP, which won a second term in 1996. More scandals dogged the party, most notably the fast ferry scandal involving the province trying to develop the shipbuilding industry in British Columbia. An allegation (never substantiated) that the premier had received a favour in return for granting a gaming licence led to Clark’s resignation as premier. He was succeeded on an interim basis by Dan Miller who was in turn followed by Ujjal Dosanjh following a leadership convention.

In the 2001 provincial election, Gordon Campbell’s Liberals defeated the NDP, gaining 77 out of 79 total seats in the provincial legislature. Campbell instituted various reforms and removed some of the NDP’s policies including scrapping the “fast ferries” project, lowering income taxes, and the controversial sale of BC Rail to Canadian National Railway. Campbell was also the subject of criticism after he was arrested for driving under the influence during a vacation in Hawaii, but he still managed to lead his party to victory in the 2005 provincial election against a substantially strengthened NDP opposition. Campbell won a third term in the 2009 provincial election, marking the first time in 23 years a premier has been elected to a third term.

The province won a bid to host the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver and Whistler. As promised in his 2002 re-election campaign, Vancouver Mayor Larry Campbell staged a non-binding civic referendum regarding the hosting of the Olympics. In February 2003, Vancouver’s residents voted in a referendum accepting the responsibilities of the host city should it win its bid. Sixty-four percent of residents voted in favour of hosting the games.[78]

After the Olympic joy had faded, Campbell’s popularity started to fall. His management style, the implementation of the Harmonized Sales Tax (HST) against election promises and the cancelling of the BC Rail corruption trial led to low approval ratings and loss of caucus support. He resigned in November 2010 and called on the party to elect a new leader.[79]

In early 2011, former deputy premier Christy Clark became leader of the Liberal Party. Though she was not a sitting MLA, she went on to win the seat left vacant by Campbell. For the next two years, she attempted to distance herself from the unpopularity of Campbell and forge an image for the upcoming 2013 election. Among her early accomplishments were raising the minimum wage, creating a new statutory holiday in February called “Family Day”, and pushing the development of BC’s liquefied natural gas industry. In the lead-up to the 2013 election, the Liberals lagged behind the NDP by a double-digit gap in the polls, but were able to achieve a surprise victory on election night, winning a majority and making Clark the first woman to lead a party to victory in a general election in BC.[80] While Clark lost her seat to NDP candidate David Eby, she later won a by-election in the riding of Westside-Kelowna. Her government went on to balance the budget, implement changes to liquor laws and continue with the question of the proposed Enbridge Northern Gateway Pipelines.

In the 2017 election, the NDP formed a minority government with the support of the Green Party through a confidence and supply agreement. The NDP and Green caucuses together controlled 44 seats, compared to the Liberals’ 43. On July 18, 2017, NDP leader John Horgan was sworn in as the premier of British Columbia. He was the province’s first NDP premier in 16 years. Clark resigned shortly thereafter, and Andrew Wilkinson was voted to become leader of the BC Liberals. In late 2020, Horgan called an early election. In the 2020 British Columbia general election, the NDP won 57 seats and formed a majority government, making Horgan the first NDP premier to be re-elected in the province. Wilkinson resigned as the leader of the BC Liberals two days later.

British Columbia was significantly affected by demographic changes within Canada and around the world. Vancouver (and to a lesser extent some other parts of British Columbia) was a major destination for many of the immigrants from Hong Kong who left the former UK colony (either temporarily or permanently) in the years immediately prior to its handover to China. British Columbia has also been a significant destination for internal Canadian migrants. This has been the case throughout recent decades,[when?] because of its natural environment, mild climate and relaxed lifestyle, but has been particularly true during periods of economic growth.[citation needed] British Columbia has moved from approximately 10 percent of Canada’s population in 1971 to approximately 13 percent in 2006. Trends of urbanization mean the Greater Vancouver area now includes 51 percent of the province’s population, followed by Greater Victoria with 8 percent. These two metropolitan regions have traditionally dominated the demographics of BC.

By 2018, housing prices in Vancouver were the second-least affordable in the world, behind only Hong Kong.[81] Many experts point to evidence of money-laundering from mainland China as a contributing factor. The high price of residential real estate has led to the implementation of an empty homes tax, a housing speculation and vacancy tax, and a foreign buyers’ tax on housing.[82]

The net number of people coming to BC from other provinces in 2016 was almost four times larger than in 2012. BC was the largest net recipient of interprovincial migrants in Canada in the first quarter of 2016 with half of the 5,000 people coming from Alberta.[83]

By 2021, the COVID-19 pandemic had had a major effect on the province,[84] with over 2,000 deaths and 250,000 confirmed cases. However, the COVID-19 vaccine reduced the spread of the virus, with 78 percent of people in BC over the age of five having been fully vaccinated.

In 2021, the unmarked gravesites of hundreds of Indigenous children were discovered at three former Indian residential schools (Kamloops, St. Eugene’s Mission, Kuper Island).[85][86]

Demographics[edit]

Population[edit]

Population density map of British Columbia, with regional district borders shown

Statistics Canada’s 2021 Canadian census recorded a population of 5,000,879 — making British Columbia Canada’s third-most populous province after Ontario and Quebec.[5][87]

[88][89]

Cities[edit]

Half of all British Columbians live in the Metro Vancouver Regional District, which includes Vancouver, Surrey, Burnaby, Richmond, Coquitlam, Langley (district municipality), Delta, North Vancouver (district municipality), Maple Ridge, New Westminster, Port Coquitlam, North Vancouver (city), West Vancouver, Port Moody, Langley (city), White Rock, Pitt Meadows, Bowen Island, Anmore, Lions Bay, and Belcarra, with adjacent unincorporated areas (including the University Endowment Lands) represented in the regional district as the electoral area known as Greater Vancouver Electoral Area A. The metropolitan area has seventeen Indian reserves, but they are outside of the regional district’s jurisdiction and are not represented in its government.

The second largest concentration of British Columbia population is at the southern tip of Vancouver Island, which is made up of the 13 municipalities of Greater Victoria, Victoria, Saanich, Esquimalt, Oak Bay, View Royal, Highlands, Colwood, Langford, Central Saanich/Saanichton, North Saanich, Sidney, Metchosin, Sooke, which are part of the Capital Regional District. The metropolitan area also includes several Indian reserves (the governments of which are not part of the regional district). Almost half of the Vancouver Island population is in Greater Victoria.

Ten largest metropolitan areas by population[90][c]

#

Metropolitan area

2021[91]

2016

2011

1

Vancouver

2,642,825

2,463,431

2,313,328

2

Victoria

397,237

367,770

344,615

3

Kelowna

222,162

194,882

179,839

4

Abbotsford

195,726

180,518

170,191

5

Nanaimo

115,459

104,936

98,021

6

Kamloops

114,142

103,811

98,754

7

Chilliwack

113,767

101,512

92,308

8

Prince George

89,490

86,622

84,232

9

Vernon

67,086

61,334

58,584

10

Courtenay

63,282

54,157

55,213

Ten largest municipalities by population

#

Municipality

2021[91]

2016

2011

1

Vancouver

662,248

631,486

603,502

2

Surrey

568,322

517,887

468,251

3

Burnaby

249,125

232,755

223,218

4

Richmond

209,937

198,309

190,473

5

Abbotsford

153,524

141,397

133,497

6

Coquitlam

148,625

139,284

126,456

7

Kelowna

144,576

127,380

117,312

8

Langley

132,603

117,285

104,177

9

Saanich

117,735

114,148

109,752

10

Delta

108,455

102,238

99,863

Cultural origins[edit]

British Columbia is the most diverse province in Canada; as of 2016, the province had the highest proportion of visible minorities in the country. The five largest pan-ethnic groups in the province are Europeans (64 percent), East Asians (15 percent), South Asians (8 percent), Aboriginals (6 percent) and Southeast Asians (4 percent).[16]

Top ethnic origins in BC (2016 census)[16][d]

#

Ethnic origin

Population

Percent

1

English

1,203,540

26.39%

2

Canadian

866,530

19%

3

Scottish

860,775

18.88%

4

Irish

675,135

14.80%

5

German

603,265

13.23%

6

Chinese

540,155

11.84%

7

French

388,815

8.53%

8

Indian

309,315

6.78%

9

Ukrainian

229,205

5.03%

10

Indigenous Canadian

220,245

4.83%

Religion[edit]

According to the 2021 census, religious groups in British Columbia included:[92]

Irreligion (2,559,250 persons or 52.1%)

Christianity (1,684,870 persons or 34.3%)

Sikhism (290,870 persons or 5.9%)

Islam (125,915 persons or 2.6%)

Buddhism (83,860 persons or 1.7%)

Hinduism (81,320 persons or 1.7%)

Judaism (26,850 persons or 0.5%)

Indigenous spirituality (11,570 persons or 0.2%)

Other (51,440 persons or 1.0%)

Language[edit]

As of the 2021 Canadian Census, the ten most spoken languages in the province included English (4,753,280 or 96.69%), French (327,350 or 6.66%), Punjabi (315,000 or 6.41%), Mandarin (312,625 or 6.36%), Cantonese (246,045 or 5.01%), Spanish (143,900 or 2.93%), Hindi (134,950 or 2.75%), Tagalog (133,780 or 2.72%), German (84,325 or 1.72%), and Korean (69,935 or 1.42%).[93] The question on knowledge of languages allows for multiple responses.

Of the 4,648,055 population counted by the 2016 census, 4,598,415 people completed the section about language. Of these, 4,494,995 gave singular responses to the question regarding their first language. The languages most commonly reported were the following:

Most common reported mother tongue in BC (2016)[19]

#

Language

Population

Percent

1

English

3,170,110

70.52%

2

Punjabi

198,805

4.42%

3

Cantonese

193,530

4.31%

4

Mandarin

186,325

4.15%

5

Tagalog (Filipino)

78,770

1.75%

6

German

66,885

1.49%

7

French

55,325

1.23%

8

Korean

52,160

1.17%

9

Spanish

47,010

1.05%

10

Persian

43,470

0.97%

While these languages all reflect the last centuries of colonialism and recent immigration, British Columbia is home to 34 Indigenous languages.[94] They are spoken by about 6000 people in total,[95] with 4000 people fluent in their Indigenous languages. They are members of the province’s First Nations. One of the main Indigenous languages in BC is Kwakʼwala, the language of the Kwakwakaʼwakw First Nations.

Economy[edit]

BC’s economy is diverse, with service-producing industries accounting for the largest portion of the province’s GDP.[96] It is the terminus of two transcontinental railways, and the site of 27 major marine cargo and passenger terminals. Though less than 5 percent of its vast 944,735 square kilometres (364,764 sq mi) land is arable, the province is agriculturally rich (particularly in the Fraser and Okanagan valleys), because of milder weather near the coast and in certain sheltered southern valleys. Its climate encourages outdoor recreation and tourism, though its economic mainstay has long been resource extraction, principally logging, farming, and mining. Vancouver, the province’s largest city, serves as the headquarters of many western-based natural resource companies. It also benefits from a strong housing market and a per capita income well above the national average. While the coast of British Columbia and some valleys in the south-central part of the province have mild weather, the majority of its land mass experiences a cold-winter-temperate climate similar to the rest of Canada. The Northern Interior region has a subarctic climate with very cold winters. The climate of Vancouver is by far the mildest winter climate of the major Canadian cities, with nighttime January temperatures averaging above the freezing point.[97]

British Columbia has a history of being a resource dominated economy, centred on the forestry industry but also with fluctuating importance in mining. Employment in the resource sector has fallen steadily as a percentage of employment, and new jobs are mostly in the construction and retail/service sectors. It now has the highest percentage of service industry jobs in the west, constituting 72 percent of industry (compared to 60 percent Western Canadian average).[98] The largest section of this employment is in finance, insurance, real estate and corporate management; however, many areas outside of metropolitan areas are still heavily reliant on resource extraction. With its film industry known as Hollywood North, the Vancouver region is the third-largest feature film production location in North America, after Los Angeles and New York City.[99]

The economic history of British Columbia is replete with tales of dramatic upswings and downswings, and this boom and bust pattern has influenced the politics, culture and business climate of the province. Economic activity related to mining in particular has widely fluctuated with changes in commodity prices over time, with documented costs to community health.[100]

In 2020, British Columbia had the third-largest GDP in Canada, with a GDP of $309 billion and a GDP per capita of $60,090.[101][102] British Columbia’s debt-to-GDP ratio is edging up to 15.0 percent in fiscal year 2019–20, and it is expected to reach 16.1 percent by 2021–22.[103][104] British Columbia’s economy experienced strong growth in recent years with a total growth rate of 9.6% from 2017 to 2021, a growth rate that was second in the country.[105]

Government and politics[edit]

The British Columbia Parliament Buildings in Victoria

The lieutenant governor, Janet Austin, is the Crown’s representative in the province. During the absence of the lieutenant governor, the Governor in Council (federal Cabinet) may appoint an administrator to execute the duties of the office. This is usually the chief justice of British Columbia.[106] British Columbia is divided into regional districts as a means to better enable municipalities and rural areas to work together at a regional level.

British Columbia has an 87-member elected Legislative Assembly, elected by the plurality voting system, though from 2003 to 2009 there was significant debate about switching to a single transferable vote system called BC-STV. The government of the day appoints ministers for various portfolios, what are officially part of the Executive Council, of whom the premier is chair.

The province is currently governed by the British Columbia New Democratic Party (BC NDP) under Premier David Eby. The 2017 provincial election saw the Liberal Party take 43 seats, the NDP take 41, and the British Columbia Green Party take 3. No party met the minimum of 44 seats for a majority, therefore leading to the first minority government since 1953. Following the election, the Greens entered into negotiations with both the Liberals and NDP, eventually announcing they would support the current NDP minority. Previously, the right-of-centre British Columbia Liberal Party governed the province for 16 years between 2001 and 2017, and won the largest landslide election in British Columbia history in 2001, with 77 of 79 seats. The legislature became more evenly divided between the Liberals and NDP following the 2005 (46 Liberal seats of 79) and 2009 (49 Liberal seats of 85) provincial elections. The NDP and its predecessor the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) have been the main opposition force to right-wing parties since the 1930s and have ruled with majority governments in 1972–1975 and 1991–2001. The Green Party plays a larger role in the politics of British Columbia than Green parties do in most other jurisdictions in Canada. After a breakthrough election in 2001 (12.39 percent), the party’s vote share declined (2005 – 9.17 percent, 2009 – 8.09 percent, 2013 – 8.13 percent) before increasing again to a record high of 16.84 percent at the 2017 election.

The British Columbia Liberal Party is not related to the federal Liberal Party and does not share the same ideology. Instead, the BC Liberal party is a rather diverse coalition, made up of the remnants of the Social Credit Party, many federal Liberals, federal Conservatives, and those who would otherwise support right-of-centre or free enterprise parties. Historically, there have commonly been third parties present in the legislature (including the Liberals themselves from 1952 to 1975); the BC Green Party are the current third party in British Columbia, with three seats in the legislature.

Prior to the rise of the Liberal Party, British Columbia’s main political party was the British Columbia Social Credit Party which ruled British Columbia for 20 continuous years. While sharing some ideology with the current Liberal government, they were more right-wing although undertook nationalization of various important monopolies, notably BC Hydro and BC Ferries.

The meeting chamber of the Legislative Assembly

British Columbia is known for having politically active labour unions who have traditionally supported the NDP or its predecessor, the CCF.