Fictional poet and literary hoax

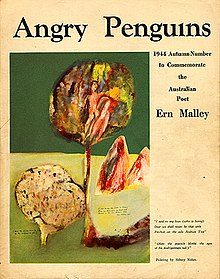

The Ern Malley edition of Angry Penguins. Featured on the cover is a Sidney Nolan painting inspired by lines from Ern Malley’s poem Petit Testament, which are printed on the cover, bottom right: “I said to my love (who is living) / Dear we shall never be that verb / Perched on the sole Arabian Tree / (Here the peacock blinks the eyes of his multipennate tail)”. The painting is now held at the Heide Museum of Modern Art.[1]

The Ern Malley hoax, also called the Ern Malley affair, is Australia’s most famous literary hoax.[2][3][4] Its name derives from Ernest Lalor “Ern” Malley, a fictitious poet whose biography and body of work were created in one day in 1943 by conservative writers James McAuley and Harold Stewart in order to hoax the Angry Penguins, a modernist art and literary movement centred around a journal of the same name, co-edited by poet Max Harris and art patron John Reed, of Heide, Melbourne.

Imitating the modernist poetry they despised, the hoaxers deliberately created what they thought was bad verse and mailed sixteen poems to Harris under the guise of Ethel, Ern Malley’s surviving sister. Harris and other members of the Heide Circle fell for the hoax, and, enraptured by the poetry, devoted the next issue of Angry Penguins to Malley, hailing him as a genius. The hoax was revealed soon after, resulting in a cause célèbre and the humiliation of Harris, who was put on trial, convicted and fined for publishing the poems on the grounds that they contained obscene content. Angry Penguins folded in 1946.

In the decades that followed, the hoax proved to be a significant setback for modernist poetry in Australia. Since the 1970s, however, the Ern Malley poems, though known to be a hoax, became celebrated as a successful example of surrealist poetry in their own right, lauded by poets and critics such as John Ashbery, Kenneth Koch and Robert Hughes. The poems of Ern Malley are now more widely read than those of his creators, and the affair has inspired works by major Australian writers and artists, such as Peter Carey and Sidney Nolan. American poet and anthologist David Lehman called Ern Malley “the greatest literary hoax of the twentieth century”.[2]

Background[edit]

James McAuley and Harold Stewart were both, in 1944, in the Army Directorate of Research and Civil Affairs. Before the war they had been part of Sydney’s Bohemian arts world. McAuley had acted and sung in left-wing revues at Sydney University.

Harris was a 22-year-old avant-garde poet and critic in Adelaide, who in 1940, at the age of 18, had started Angry Penguins.[5]

Creating the hoax[edit]

James McAuley, 1944Harold Stewart, 1944

McAuley and Stewart decided to perpetrate a hoax on Harris and Angry Penguins by submitting to the magazine nonsensical poetry, which they felt captured the worst of modernist tendencies, under the guise of a fictional poet. They came up with a fictional biography for the poet “Ernest Lalor Malley”, who, they claimed, had died the year before at the age of 25. The name is a “highly Australian-sounding handle”: “Malley” is a pun on the word mallee, denoting a class of Australian vegetation and a bird, the native malleefowl, and “Lalor” recalls Peter Lalor, leader of the 1854 Eureka Rebellion. Then, in one afternoon, they wrote his entire body of work: 17 poems, none longer than a page, and all intended to be read in sequence under the title The Darkening Ecliptic.

Their writing style, as they described it, was to write down the first thing that came into their heads, lifting words and phrases from the Concise Oxford Dictionary, a Collected Shakespeare, and a Dictionary of Quotations: “We opened books at random, choosing a word or phrase haphazardly. We made lists of these and wove them in nonsensical sentences. We misquoted and made false allusions. We deliberately perpetrated bad verse, and selected awkward rhymes from a Ripman’s Rhyming Dictionary.”[7] They also included many bits of their own poetry, though in a deliberately disjointed manner.

The first poem in the sequence, Durer: Innsbruck, 1495, was an unpublished serious effort by McAuley, edited to appeal to Harris:

I had often cowled in the slumbrous heavy air,Closed my inanimate lids to find it real,As I knew it would be, the colourful spiresAnd painted roofs, the high snows glimpsed at the back,All reversed in the quiet reflecting waters –Not knowing then that Durer perceived it too.Now I find that once more I have shrunkTo an interloper, robber of dead men’s dream,I had read in books that art is not easyBut no one warned that the mind repeatsIn its ignorance the vision of others. I am stillThe black swan of trespass on alien waters.

David Brooks theorises in his 2011 book, The Sons of Clovis: Ern Malley, Adoré Floupette and a Secret History of Australian Poetry, that the Ern Malley hoax was modelled on the 1885 satire on French Symbolism and the Decadent movement, Les Déliquescences d’Adoré Floupette, by Henri Beauclair and Gabriel Vicaire.[8] Stewart claimed to have never heard of Floupette at the time of the Ern Malley hoax, and while there is no evidence McAuley had, his Masters thesis titled “Symbolism: an essay in poetics”, included a study of French Symboliste poetry and poetics.[9]

Biography of “Ern Malley”[edit]

Ernest Lalor MalleyBornErnest Lalor Malley(1918-03-14)14 March 1918Liverpool, EnglandDied23 July 1943(1943-07-23) (aged 25)Sydney, AustraliaNationalityBritishKnown forPoetryNotable workThe Darkening Ecliptic

According to his inventors’ fictitious biography, Ernest Lalor Malley was born in Liverpool, England, on 14 March 1918. His father died in 1920, and Malley’s mother migrated to Petersham, a suburb of Sydney, Australia, with her two children: Ern, and his older sister Ethel. After his mother’s death in August 1933, Ern Malley left school to work as an auto mechanic. Shortly after his seventeenth birthday, he then moved to Melbourne where he lived alone and worked as an insurance salesman, and later as a watch repairman. Diagnosed with Graves’ disease sometime in the early 1940s, Malley refused treatment. He returned to Sydney, moving in with his sister in March, 1943, where he became increasingly ill (as well as temperamental and difficult) until his death at the age of 25 on 23 July of that same year.

Malley’s life as a poet became known only after his sister Ethel (another fictitious creation of McAuley and Stewart) found a pile of unpublished poems among his belongings. These poems featured a brief preface, which explained that they had been composed over a period of five years, but it left no instructions as to what was to be done with them. Ethel Malley supposedly knew nothing about poetry, but showed the poems to a friend, who suggested that she send the poems to someone who could examine them.[10] Max Harris of Angry Penguins was to be that someone.

Carrying out the hoax[edit]

McAuley and Stewart then sent Harris a letter, purported to be from Ethel, containing the poems, and asking for his opinion of her late brother’s work.

Harris read the poems with, as he later recalled, a mounting sense of excitement. Ern Malley, he thought, was a poet in the same class as W. H. Auden or Dylan Thomas. He showed them to his circle of literary friends, who agreed that a hitherto completely unknown modernist poet of great importance had been discovered in suburban Australia. He decided to rush out a special edition of Angry Penguins and commissioned a painting by Sidney Nolan, based on the poems, for the cover.[5]

The Autumn 1944 edition of Angry Penguins appeared in June 1944 owing to wartime printing delays. Harris eagerly promoted it around the small world of Australian writers and critics. The reaction was not what he had hoped or expected. An article appeared in the University of Adelaide student newspaper, On Dit, ridiculing the Malley poems and suggesting that Harris had written them himself in some elaborate hoax.

The hoax revealed[edit]

On 17 June, the Adelaide Daily Mail raised the possibility that Harris was the hoaxed rather than the hoaxer. Alarmed, Harris hired a private detective to establish whether Ern and Ethel Malley existed or had ever done so, but by then, the Australian national press was on the trail. The next week, the Sydney Sunday Sun, which had been conducting some investigative reporting, ran a front-page story alleging that the Ern Malley poems had in fact been written by McAuley and Stewart.[12]

The South Australian police impounded the issue of Angry Penguins devoted to The Darkening Ecliptic on the grounds that Malley’s poems were obscene.[2]

After the hoax was revealed, McAuley and Stewart wrote:

Mr. Max Harris and other Angry Penguins writers represent an Australian outcrop of a literary fashion which has become prominent in England and America. The distinctive feature of the fashion, it seemed to us, was that it rendered its devotees insensible of absurdity and incapable of ordinary discrimination. Our feeling was that by processes of critical self-delusion and mutual admiration, the perpetrators of this humourless nonsense had managed to pass it off on would-be intellectuals and Bohemians, both here and abroad, as great poetry. … However, it was possible that we had simply failed to penetrate to the inward substance of these productions. The only way of settling the matter was by way of experiment. It was, after all, fair enough. If Mr Harris proved to have sufficient discrimination to reject the poems, then the tables would have been turned.[7]

Immediate impact[edit]

The South Australian police prosecuted Harris for publishing immoral and obscene material. The only prosecution witness was a police detective, whose evidence included the statement ‘I don’t know what “incestuous” means, but I think there is a suggestion of indecency about it'”. Despite this, and several distinguished expert witnesses arguing for Harris, he was found guilty and fined £5.[13] Angry Penguins soon folded.

Most people, including most educated people with an interest in the arts, were persuaded of the validity of McAuley and Stewart’s “experiment”. The two had deliberately written bad poetry, passed it off under a plausible alias to the country’s most prominent publisher of modernist poetry, and completely taken him in. Harris, they said, could not tell real poetry from fake, good from bad.

The Ern Malley hoax had long-lasting repercussions. To quote the Oxford Companion to Australian Literature, “More important than the hoax itself was the effect it had on the development of Australian poetry. The vigorous and legitimate movement for modernism in Australian writing, espoused by many writers and critics in addition to the members of the Angry Penguins group, received a severe setback, and the conservative element was undoubtedly strengthened.”[14]

In a 1975 interview with Earle Hackett, Sidney Nolan credited Ern Malley with inspiring him to paint his first Ned Kelly series (1946–47), saying “It made me take the risk of putting against the Australian bush an utterly strange object.”[1]

McAuley, Stewart and Harris in later years[edit]

McAuley went on to publish several volumes of poetry and, with Richard Krygier, founded the literary and cultural journal Quadrant. From 1961 he was professor of English at the University of Tasmania. He died in 1976.[15]

Stewart settled permanently in Japan in 1966 and published two volumes of haiku poetry translations which became popular in Australia. He died in 1995.

Harris, however, once he recovered from his humiliation in the Ern Malley hoax, made the best of his notoriety. From 1951 to 1955, he published another literary magazine, which he called Ern Malley’s Journal. In 1961, as a gesture of defiance, he re-published the Ern Malley poems, maintaining that whatever McAuley and Stewart had intended to do, they had, in fact, produced some memorable poems. Harris went on to become a successful bookseller and newspaper columnist. Harris died in 1995.

Subsequent re-appreciation[edit]

The fictional Ern Malley achieved a measure of celebrity. The poems are regularly re-published and quoted. There have been at least 20 publications of the Darkening Ecliptic, either complete or partial. It has reappeared – not only in Australia, but in London, Paris, Lyons, Kyoto, New York and Los Angeles – with a regularity that would be the envy of any real Australian poet.[16]

Some literary critics take the view that McAuley and Stewart outsmarted themselves in their concoction of the Ern Malley poems. “Sometimes the myth is greater than its creators,” Max Harris wrote. Harris, of course, had a vested interest in Malley, but others have agreed with his assessment. Robert Hughes wrote:

The basic case made by Ern’s defenders was that his creation proved the validity of surrealist procedures: that in letting down their guard, opening themselves to free association and chance, McAuley and Stewart had reached inspiration by the side-door of parody; and though this can’t be argued on behalf of all the poems, some of which are partly or wholly gibberish, it contains a ponderable truth… The energy of invention that McAuley and Stewart brought to their concoction of Ern Malley created an icon of literary value, and that is why he continues to haunt our culture.[This quote needs a citation]

In the “Individual Notes on Works and Authors” in the “Special Collaborations Issue” of Locus Solus, Kenneth Koch wrote, “Though Harris was wrong about who Ern Malley ‘was’ (if one can use that word here), I find it hard not to agree with his judgment of Malley’s poetry.”

The American poet John Ashbery said of Ern Malley, in a 1988 interview in the magazine Jacket:

I think it was the first summer I was at Harvard as a student, and I discovered a wonderful bookstore there where I could get modern poetry – which I’d never been able to lay my hands on very much until then – and they had the original edition of The Darkening Ecliptic with the Sidney Nolan cover. […] I always had a taste for sort of wild experimental poetry – of which there really wasn’t very much in English in America at the time – and this poet suited me very well. […] I am obliged to give a final examination in my poetry writing course [at Brooklyn College, NY], which I’m always rather hard put to do, since we haven’t really studied anything. The students have been writing poems of varying degrees of merit, and though I give them reading lists they tend to ignore them, after first demanding them. And the way the course is set up there is no way of examining them on their reading. And anyway they shouldn’t have to pass an examination because they’re poets who are writing poetry, and I don’t like the idea of grading poems. So in order to pass the examination time I had to think of various subterfuges, and one of them is to use one of Malley’s poems and another forbiddingly modern poem – frequently one of Geoffrey Hill’s ‘Mercian Hymns’. And asking them if they can guess which one is the real poem by a respected contemporary poet, and which one is a put-on intended to ridicule modern poetry, and what are their reasons. And I think they are right about fifty per cent of the time, identifying the fraud… [the] fraudulent poem.[17]

Two exhibitions by major Australian galleries have been based on Ern Malley. In 1974 the Art Gallery of South Australia’s Adelaide Festival Exhibitions included the Sidney Nolan exhibition “Ern Malley and Paradise Garden”. The 2009 exhibition “Ern Malley: The Hoax and Beyond” at Heide Museum of Modern Art was the first exhibition to thoroughly investigate the genesis, reception and aftermath of the hoax.[18]

It has been suggested that Malley is better known and more widely read today than either McAuley or Stewart.[19][9][20][21]

In The Washington Post, David Lehman wrote,

The Ern Malley affair was the century’s greatest literary hoax not because it completely hookwinked Harris and not because it triggered off a story so rich in ironies and reversals. It was the greatest hoax because the creation of Ern Malley escaped the control of his creators and enjoyed an autonomous existence beyond, and at odds with, the critical and satirical intentions of McAuley and Stewart. They succeeded better than they had known, or wished. Malley’s poems hold up to this day, eclipsing anything produced by any of the story’s main protagonists in propria persona.[22]

References to Ern Malley and the hoax[edit]

The Australian historian Humphrey McQueen alluded to the poems in calling his 1979 history of modernism in Australia The Black Swan of Trespass.

Several works of fiction attribute the poems to a third party who actually wrote them; they then fall into the hands of McAuley and Stewart. In 1977 in Overland, Barbara Ker Wilson wrote a short story “Black Swan of Trespass”, in which she has Davydd Davis, who presents as an antipodean Dylan Thomas, writing the poems. Malarky Dry, by Ian Kennedy Williams, was published in 1990 and tells of a sickly, insipid Ern who writes a manual of motorcycle maintenance while a boring bureaucrat Henry Fitzhubert-Ireland writes the poems.[23] Two more recent fictions invent a “real” Ern: “Strangers in the House of the Mind” which appears in Martin Edmond’s 2007 collection Waimarino County & Other Excursions,[24] and David Malley’s Beyond is Anything.[25][26]

Joanna Murray-Smith’s play Angry Young Penguins (1987) is based on these events.

Peter Carey’s 2003 novel My Life as a Fake draws some of its inspiration from the Ern Malley affair. Elliot Perlman recounts the tale of the Ern Malley hoax in his 2003 novel Seven Types of Ambiguity. In 2005, The Black Swan of Trespass, a surrealist play about the real life of a fictional Ern Malley by Lally Katz and Chris Kohn, premiered at the Melbourne Malthouse Theatre.

In the early years of the 21st century, the artist Garry Shead produced a series of well-received paintings based on the Ern Malley hoax.

In the 2013 novel Cairo, after the success of a fictionalized version of the theft of the one of Picasso’s studies for The Weeping Woman, one of characters quotes Malley’s Durer: Innsbruck, 1495.[27]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

^ a b c Pearce, Barry. Sidney Nolan. Sydney: Art Gallery of New South Wales, 2007. ISBN 1-74174-013-4, pp. 96–97

^ a b c Lehman D., 1998. “The Ern Malley Poetry Hoax – Introduction” in Jacket, No. 17

^ “Throwing new light on the great Ern Malley hoax”, Sydney Writers’ Festival, 14 May 2012, University of Sydney

^ “Ern Malley literary hoax”, 80 Days that Changed Our Life, 27 October 2011, ABC Archives

^ a b Malley, Ern (2017). The Darkening Ecliptic. Los Angeles: Green Integer. ISBN 978-1-55713-439-4.

^ a b “Ern Malley, Poet of Debunk: full story from the two authors”. Fact. Jacket (Collection of quotations by McAuley and Stewart). No. 17. June 2002. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

^ “Ern, it turns out, has a French cousin” by Don Anderson, The Australian (1–2 October 2011)

^ a b Heyward, Michael (June 2002). “The Ern Malley Affair”. Jacket (Excerpt of Heyward’s book). No. 17. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

^ Documentation of Ethel’s action and other sources: Ern Malley feature edition, Jacket (Sydney), No. 7, June 2002, ed. John Tranter

^ “Ern Malley, the great poet, or the greatest hoax?”. Supplement to The Sunday Sun and Guardian. The Sun. No. 2151. New South Wales, Australia. 18 June 1944. p. 1. Retrieved 17 October 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

^ Collected Poems: Ern Malley. Angus & Robertson Childrens. 1993. ISBN 0207179778.

^ Wilde, William H.; Hooton, Joy; Andrews, Barry, eds. (1994). “Ern Malley Hoax”. Oxford Companion to Australian Literature. Oxford University Press. p. 257. ISBN 9780195533811.

^ Pierce, Peter (2000). “McAuley, James Phillip (1917–1976)”. Australian Dictionary of Biography. Vol. 15. Melbourne University Press. ISSN 1833-7538 – via National Centre of Biography, Australian National University.

^ Rainey, David. Ern Malley: The Hoax and Beyond. Melbourne: Heide Museum of Modern Art, 2009. ISBN 978-1-921330-10-0, pp. 30–32.

^ “John Ashbery in conversation with John Tranter New York City, May 1988”. Jacket. No. 2. January 1998. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

^ Rainey, David (24 July 2012). “Ern Malley: The Hoax and Beyond”. aCOMMENT. Retrieved 24 July 2014.

^ Pádraig Collins (3 September 2003). “The poet who never was”. The Irish Times.

^ Critical Analysis and Reasoning Skills (PDF) (MCAT exam). 2015. p. 206.

^ “Trolls before their time”, dailycare.com.au

^ “The poet who never was”, review of Heyward’s The Ern Malley Affair by David Lehman, The Washington Post, 6 March 1994

^ Kennedy Williams, Ian (1990). Malarky Dry. Sydney: Hale & Ironmonger. ISBN 0-86806-393-2.

^ Edmond, Martin (2007). Waimarino County & Other Excursions. Auckland University Press. p. 174. ISBN 978-1-86940-391-1.

^ Malley, David (2009). Beyond is Anything. Croydon, NSW: Self published. ISBN 978-0-646-48866-0.

^ Rainey, David (24 June 2012). “Beyond is Anything”. aCOMMENT. Retrieved 19 July 2014.

^ Chris Womersley (2014). Cairo. Quercus Books. p. 249. ISBN 9781743530665.

Sources

Heyward, Michael (1993). The Ern Malley Affair. University of Queensland Press.

Further reading[edit]

David Lewis, Ern Malley’s Namesake, Quadrant, 39 (3) (March 1995), 14-15

Brooks, David (2011). The Sons of Clovis: Ern Malley, Adoré Floupette and a Secret History of Australian Poetry. Brisbane: University of Queensland Press. ISBN 978-0-7022-3884-0.

Ern Malley, The Darkening Ecliptic, Los Angeles: Green Integer, 2017, ISBN 978-1-55713-439-4

McQueen, H., The Black Swan of Trespass: The Emergence of Modernist Painting in Australia 1918–1944, Alternative Publishing, Sydney 1979

External links[edit]