Country in Northwestern Europe with territories in the Caribbean

Constituent country in the Kingdom of the Netherlands

|

Netherlands |

|

|---|---|

| Motto: | |

| Anthem: Wilhelmus (Dutch) (English: “William of Nassau”) |

|

| Sovereign state | Kingdom of the Netherlands |

| Before independence | Spanish Netherlands |

| Act of Abjuration | 26 July 1581 |

| Peace of Münster | 30 January 1648 |

| Kingdom established | 16 March 1815 |

| Liberation Day | 5 May 1945 |

| Kingdom Charter | 15 December 1954 |

| Caribbean reorganisation | 10 October 2010 |

| Capital

and largest city |

Amsterdam[a] 52°22′N 4°53′E / 52.367°N 4.883°E / 52.367; 4.883 |

| Government seat | The Hague[a] |

| Official languages | Dutch |

|

Recognised languages |

|

| Ethnic groups

(2020) |

|

| Religion

(2020) |

|

| Demonym(s) | Dutch |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy |

| Willem-Alexander | |

| Mark Rutte | |

| Legislature | States General |

| Senate | |

| House of Representatives | |

| 26 seats | |

|

• Total |

41,850 km2 (16,160 sq mi) (131st) |

|

• Water (%) |

18.41 |

| Highest elevation | 887 m (2,910 ft) |

|

• 16 December 2022 estimate |

|

|

• 2011 census |

16,655,799 |

|

• Density |

423/km2 (1,095.6/sq mi) (16th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2022 estimate |

|

• Total |

|

|

• Per capita |

|

| GDP (nominal) | 2022 estimate |

|

• Total |

|

|

• Per capita |

|

| Gini (2020) | low |

| HDI (2021) | very high · 10th |

| Currency | |

| Time zone | |

| Date format | dd-mm-yyyy |

| Mains electricity | 230 V–50 Hz |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +31, +599[g] |

| ISO 3166 code | NL |

| Internet TLD | .nl, .bq[h] |

The Netherlands (Dutch: Nederland [ˈneːdərlɑnt] (![]() listen)), informally Holland, is a country located in Northwestern Europe with overseas territories in the Caribbean. It is the largest of four constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. The Netherlands consists of twelve provinces; it borders Germany to the east, and Belgium to the south, with a North Sea coastline to the north and west. It shares maritime borders with the United Kingdom, Germany and Belgium in the North Sea. The country’s official language is Dutch, with West Frisian as a secondary official language in the province of Friesland. Dutch Low Saxon and Limburgish are recognised regional languages, while Dutch Sign Language, Sinte Romani and Yiddish are recognised non-territorial languages. Dutch, English and Papiamento are official in the Caribbean territories.

listen)), informally Holland, is a country located in Northwestern Europe with overseas territories in the Caribbean. It is the largest of four constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. The Netherlands consists of twelve provinces; it borders Germany to the east, and Belgium to the south, with a North Sea coastline to the north and west. It shares maritime borders with the United Kingdom, Germany and Belgium in the North Sea. The country’s official language is Dutch, with West Frisian as a secondary official language in the province of Friesland. Dutch Low Saxon and Limburgish are recognised regional languages, while Dutch Sign Language, Sinte Romani and Yiddish are recognised non-territorial languages. Dutch, English and Papiamento are official in the Caribbean territories.

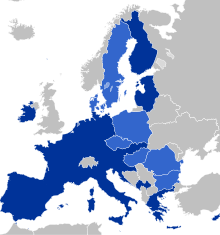

The four largest cities in the Netherlands are Amsterdam, Rotterdam, The Hague and Utrecht. Amsterdam is the country’s most populous city and the nominal capital. The Hague holds the seat of the States General, Cabinet and Supreme Court. The Port of Rotterdam is the busiest seaport in Europe. Schiphol is the busiest airport in the Netherlands, and the third busiest in Europe. The Netherlands is a founding member of the European Union, Eurozone, G10, NATO, OECD, and WTO, as well as a part of the Schengen Area and the trilateral Benelux Union. It hosts several intergovernmental organisations and international courts, many of which are centred in The Hague.

Netherlands literally means “lower countries” in reference to its low elevation and flat topography, with only about 50% of its land exceeding 1 m (3.3 ft) above sea level, and nearly 26% falling below sea level. Most of the areas below sea level, known as polders, are the result of land reclamation that began in the 14th century. In the Republican period, which began in 1588, the Netherlands entered a unique era of political, economic, and cultural greatness, ranked among the most powerful and influential in Europe and the world; this period is known as the Dutch Golden Age. During this time, its trading companies, the Dutch East India Company and the Dutch West India Company, established colonies and trading posts all over the world.

With a population of 17.7 million people, all living within a total area of 41,850 km2 (16,160 sq mi)—of which the land area is 33,500 km2 (12,900 sq mi)—the Netherlands is the 16th most densely populated country in the world and the second-most densely populated country in the European Union, with a density of 529 people per square kilometre (1,370 people/sq mi). Nevertheless, it is the world’s second-largest exporter of food and agricultural products by value, owing to its fertile soil, mild climate, intensive agriculture, and inventiveness.[31][32]

The Netherlands has been a parliamentary constitutional monarchy with a unitary structure since 1848. The country has a tradition of pillarisation and a long record of social tolerance, having legalised abortion, prostitution and human euthanasia, along with maintaining a liberal drug policy. The Netherlands abolished the death penalty in Civil Law in 1870, though it was not completely removed until a new constitution was approved in 1983. The Netherlands allowed women’s suffrage in 1919 and was the first country to legalise same-sex marriage in 2001. Its mixed-market advanced economy has the twelfth-highest per capita income globally. The Netherlands ranks among the highest in international indices of press freedom,[33] economic freedom,[34] human development and quality of life, as well as happiness.[35][36]

Etymology

Netherlands and the Low Countries

The region called the Low Countries (comprising Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg) has the same toponymy. Place names with Neder, Nieder, Nedre, Nether, Lage(r) or Low(er) (in Germanic languages) and Bas or Inferior (in Romance languages) are in use in low-lying places all over Europe. In the case of the Low Countries / Netherlands, the geographical location of the lower region has been more or less downstream and near the sea. The Romans made a distinction between the Roman provinces of downstream Germania Inferior (nowadays part of Belgium and the Netherlands) and upstream Germania Superior. The designation ‘Low’ returned in the 10th-century Duchy of Lower Lorraine, which covered much of the Low Countries.[37][38]

The Dukes of Burgundy used the term les pays de par deçà (“the lands over here”) for the Low Countries.[39] Under Habsburg rule, Les pays de par deçà developed in pays d’embas (“lands down-here”).[40] This was translated as Neder-landen in contemporary Dutch official documents.[41] From a regional point of view, Niderlant was also the area between the Meuse and the lower Rhine in the late Middle Ages. From the mid-sixteenth century, the “Low Countries” and the “Netherlands” lost their original deictic meaning.

In most Romance languages, the term “Low Countries” is officially used as the name for the Netherlands.

Holland and Dutch

The Netherlands is informally referred to as Holland in various languages, including Dutch[42] and English. In other languages, Holland is the formal name for the Netherlands. Holland can also refer to a region within the Netherlands that consists of North and South Holland. Formerly these were a single province, and earlier the County of Holland, a remnant of the dissolved Frisian Kingdom that also included parts of present-day Utrecht. Following the decline of the Duchy of Brabant and the County of Flanders, Holland became the most economically and politically important county in the Low Countries region. The emphasis on Holland during the formation of the Dutch Republic, the Eighty Years’ War, and the Anglo-Dutch Wars in the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries, made Holland a pars pro toto for the entire country.[43][44]

The term Dutch is used as the demonymic and adjectival form of the Netherlands in the English language. The origins of the word go back to Proto-Germanic *þiudiskaz, Latinised into Theodiscus, meaning “popular” or “of the people”; akin to Old Dutch Dietsch, Old High German duitsch, and Old English þeodisc, all meaning “(of) the common (Germanic) people”. At first, the English language used (the contemporary form of) Dutch to refer to any or all speakers of West Germanic languages. Gradually its meaning shifted to the West Germanic people they had the most contact with, because of their geographical proximity and rivalry in trade and overseas territories.

History

Prehistory (before 800 BC)

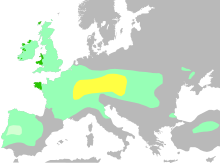

The prehistory of the area that is now the Netherlands was largely shaped by the sea and the rivers that constantly shifted the low-lying geography. The oldest human (Neanderthal) traces, believed to be about 250,000 years old, were found in higher soils near Maastricht.[45] At the end of the Ice Age, the nomadic late Upper Palaeolithic Hamburg culture (13,000–10,000 BC) hunted reindeer in the area, using spears. The later Ahrensburg culture (11,200–9,500 BC) used bow and arrow. From Mesolithic Maglemosian-like tribes (c. 8000 BC), the world’s oldest canoe was found in Drenthe.[46]

Indigenous late Mesolithic hunter-gatherers from the Swifterbant culture (c. 5600 BC), related to the southern Scandinavian Ertebølle culture, were strongly linked to rivers and open water.[47] Between 4800 and 4500 BC, the Swifterbant people started to adopt from the neighbouring Linear Pottery culture the practice of animal husbandry, and between 4300 and 4000 BC the practice of agriculture.[48] The Funnelbeaker culture (4300–2800 BC), related to the Swifterbant culture, erected the dolmens, large stone grave monuments found in Drenthe. There was a quick and smooth transition from the Funnelbeaker farming culture to the pan-European Corded Ware pastoralist culture (c. 2950 BC). In the southwest, the Seine-Oise-Marne culture — related to the Vlaardingen culture (c. 2600 BC), an apparently more primitive culture of hunter-gatherers — survived well into the Neolithic period, until it too was succeeded by the Corded Ware culture.

The subsequent Bell Beaker culture (2700–2100 BC)[49] introduced metalwork in copper, gold and later bronze and opened international trade routes not seen before, reflected in copper artifacts. Finds of rare bronze objects suggest that Drenthe was a trading centre in the Bronze Age (2000–800 BC). The Bell Beaker culture developed locally into the Barbed-Wire Beaker culture (2100–1800 BC) and later the Elp culture (1800–800 BC),[50] a Middle Bronze Age archaeological culture with earthenware low-quality pottery as a marker. The initial phase of the Elp culture was characterised by tumuli (1800–1200 BC). The subsequent phase was that of cremating the dead and placing their ashes in urns which were then buried in fields, following the customs of the Urnfield culture (1200–800 BC). The southern region became dominated by the related Hilversum culture (1800–800 BC), with apparently cultural ties with Britain of the previous Barbed-Wire Beaker culture.

Celts, Germanic tribes and Romans (800 BC–410 AD)

From 800 BC onwards, the Iron Age Celtic Hallstatt culture became influential, replacing the Hilversum culture. Iron ore brought a measure of prosperity and was available throughout the country, including bog iron. Smiths travelled from settlement to settlement with bronze and iron, fabricating tools on demand. The King’s grave of Oss (700 BC) was found in a burial mound, the largest of its kind in western Europe and containing an iron sword with an inlay of gold and coral.

The deteriorating climate in Scandinavia around 850 BC further deteriorated around 650 BC and might have triggered the migration of Germanic tribes from the North. By the time this migration was complete, around 250 BC, a few general cultural and linguistic groups had emerged.[51][52] The North Sea Germanic Ingaevones inhabited the northern part of the Low Countries. They would later develop into the Frisii and the early Saxons.[52] A second grouping, the Weser-Rhine Germanic (or Istvaeones), extended along the middle Rhine and Weser and inhabited the Low Countries south of the great rivers. This group consisted of tribes that would eventually develop into the Salian Franks.[52] Also the Celtic La Tène culture (c. 450 BC up to the Roman conquest) had expanded over a wide range, including the southern area of the Low Countries. Some scholars have speculated that even a third ethnic identity and language, neither Germanic nor Celtic, survived in the Netherlands until the Roman period, the Iron Age Nordwestblock culture,[53][54] that eventually was absorbed by the Celts to the south and the Germanic peoples from the east.

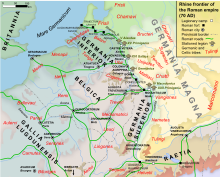

The first author to describe the coast of Holland and Flanders was the Greek geographer Pytheas, who noted in c. 325 BC that in these regions, “more people died in the struggle against water than in the struggle against men.”[55] During the Gallic Wars, the area south and west of the Rhine was conquered by Roman forces under Julius Caesar from 57 BC to 53 BC.[54] Caesar describes two main Celtic tribes living in what is now the southern Netherlands: the Menapii and the Eburones. The Rhine became fixed as Rome’s northern frontier around 12 AD. Notable towns would arise along the Limes Germanicus: Nijmegen and Voorburg. In the first part of Gallia Belgica, the area south of the Limes became part of the Roman province of Germania Inferior. The area to the north of the Rhine, inhabited by the Frisii, remained outside Roman rule (but not its presence and control), while the Germanic border tribes of the Batavi and Cananefates served in the Roman cavalry.[56] The Batavi rose against the Romans in the Batavian rebellion of 69 AD but were eventually defeated. The Batavi later merged with other tribes into the confederation of the Salian Franks, whose identity emerged in the first half of the third century.[57] Salian Franks appear in Roman texts as both allies and enemies. They were forced by the confederation of the Saxons from the east to move over the Rhine into Roman territory in the fourth century. From their new base in West Flanders and the Southwest Netherlands, they were raiding the English Channel. Roman forces pacified the region but did not expel the Franks, who continued to be feared at least until the time of Julian the Apostate (358) when Salian Franks were allowed to settle as foederati in Texandria.[57] It has been postulated that after deteriorating climate conditions and the Romans’ withdrawal, the Frisii disappeared as laeti in c. 296, leaving the coastal lands largely unpopulated for the next two centuries.[58] However, recent excavations in Kennemerland show a clear indication of permanent habitation.[59][60]

Early Middle Ages (411–1000)

After the Roman government in the area collapsed, the Franks expanded their territories into numerous kingdoms. By the 490s, Clovis I had conquered and united all these territories in the southern Netherlands in one Frankish kingdom, and from there continued his conquests into Gaul. During this expansion, Franks migrating to the south (modern territory of France and Walloon part of Belgium) eventually adopted the Vulgar Latin of the local population.[52] A widening cultural divide grew with the Franks remaining in their original homeland in the north (i.e. the southern Netherlands and Flanders), who kept on speaking Old Frankish, which by the ninth century had evolved into Old Low Franconian or Old Dutch.[52] A Dutch-French language boundary hence came into existence.[52][61]

To the north of the Franks, climatic conditions improved, and during the Migration Period Saxons, the closely related Angles, Jutes and Frisii settled the coastal land.[62] Many moved on to England and came to be known as Anglo-Saxons, but those who stayed would be referred to as Frisians and their language as Frisian, named after the land that was once inhabited by Frisii.[62] Frisian was spoken along the entire southern North Sea coast, and it is still the language most closely related to English among the living languages of continental Europe. By the seventh century, a Frisian Kingdom (650–734) under King Aldegisel and King Redbad emerged with Traiectum (Utrecht) as its centre of power,[62][63] while Dorestad was a flourishing trading place.[64][65] Between 600 and around 719 the cities were often fought over between the Frisians and the Franks. In 734, at the Battle of the Boarn, the Frisians were defeated after a series of wars. With the approval of the Franks, the Anglo-Saxon missionary Willibrord converted the Frisian people to Christianity. He established the Archdiocese of Utrecht and became the bishop of the Frisians. However, his successor Boniface was murdered by the Frisians in Dokkum, in 754.

The Frankish Carolingian empire modelled itself on the Roman Empire and controlled much of Western Europe. However, in 843, it was divided into three parts—East, Middle, and West Francia. Most of present-day Netherlands became part of Middle Francia, which was a weak kingdom and subject to numerous partitions and annexation attempts by its stronger neighbours. It comprised territories from Frisia in the north to the Kingdom of Italy in the south. Around 850, Lothair I of Middle Francia acknowledged the Viking Rorik of Dorestad as ruler of most of Frisia.[66] When the kingdom of Middle Francia was partitioned in 855, the lands north of the Alps passed to Lothair II and subsequently were named Lotharingia. After he died in 869, Lotharingia was partitioned, into Upper and Lower Lotharingia, the latter part comprising the Low Countries that technically became part of East Francia in 870, although it was effectively under the control of Vikings, who raided the largely defenceless Frisian and Frankish towns lying on the Frisian coast and along the rivers.[citation needed] Around 879, another Viking expedition led by Godfrid, Duke of Frisia, raided the Frisian lands. The Viking raids made the sway of French and German lords in the area weak. Resistance to the Vikings, if any, came from local nobles, who gained in stature as a result, and that laid the basis for the disintegration of Lower Lotharingia into semi-independent states. One of these local nobles was Gerolf of Holland, who assumed lordship in Frisia after he helped to assassinate Godfrid, and Viking rule came to an end.[citation needed]

High Middle Ages (1000–1384)

The Holy Roman Empire (the successor state of East Francia and then Lotharingia) ruled much of the Low Countries in the 10th and 11th century but was not able to maintain political unity. Powerful local nobles turned their cities, counties and duchies into private kingdoms that felt little sense of obligation to the emperor.[citation needed] Holland, Hainaut, Flanders, Gelre, Brabant, and Utrecht were in a state of almost continual war or paradoxically formed personal unions. The language and culture of most of the people who lived in the County of Holland were originally Frisian. As Frankish settlement progressed from Flanders and Brabant, the area quickly became Old Low Franconian (or Old Dutch). The rest of Frisia in the north (now Friesland and Groningen) continued to maintain its independence and had its own institutions (collectively called the “Frisian freedom“), which resented the imposition of the feudal system.[citation needed]

Around 1000 AD, due to several agricultural developments, the economy started to develop at a fast pace, and the higher productivity allowed workers to farm more land or become tradesmen. Towns grew around monasteries and castles, and a mercantile middle class began to develop in these urban areas, especially in Flanders and later also Brabant. Wealthy cities started to buy certain privileges for themselves from the sovereign. In practice, this meant that Bruges and Antwerp became quasi-independent republics in their own right and would later develop into some of the most important cities and ports in Europe.[citation needed]

Around 1100 AD, farmers from Flanders and Utrecht began draining and cultivating uninhabited swampy land in the western Netherlands, making the emergence of the County of Holland as the centre of power possible. The title of Count of Holland was fought over in the Hook and Cod Wars (Dutch: Hoekse en Kabeljauwse twisten) between 1350 and 1490. The Cod faction consisted of the more progressive cities, while the Hook faction consisted of the conservative noblemen. These noblemen invited Duke Philip the Good of Burgundy — who was also Count of Flanders — to conquer Holland.[citation needed]

Burgundian, Habsburg and Spanish Habsburg Netherlands (1384–1581)

Most of the Imperial and French fiefs in what is now the Netherlands and Belgium were united in a personal union by Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, in 1433. The House of Valois-Burgundy and their Habsburg heirs would rule the Low Countries in the period from 1384 to 1581. Before the Burgundian union, the Dutch identified themselves by the town they lived in or their local duchy or county. The Burgundian period is when the road to nationhood began. The new rulers defended Dutch trading interests, which then developed rapidly. The fleets of the County of Holland defeated the fleets of the Hanseatic League several times. Amsterdam grew and in the 15th century became the primary trading port in Europe for grain from the Baltic region. Amsterdam distributed grain to the major cities of Belgium, Northern France and England. This trade was vital because Holland could no longer produce enough grain to feed itself. Land drainage had caused the peat of the former wetlands to reduce to a level that was too low for drainage to be maintained.[citation needed]

Under Habsburg Charles V, ruler of the Holy Roman Empire and King of Spain, all fiefs in the current Netherlands region were united into the Seventeen Provinces, which also included most of present-day Belgium, Luxembourg, and some adjacent land in what is now France and Germany. In 1568, under Phillip II, the Eighty Years’ War between the Provinces and their Spanish ruler began. The level of ferocity exhibited by both sides can be gleaned from a Dutch chronicler’s report:[67]

On more than one occasion men were seen hanging their own brothers, who had been taken prisoners in the enemy’s ranks… A Spaniard had ceased to be human in their eyes. On one occasion, a surgeon at Veer cut the heart from a Spanish prisoner, nailed it on a vessel’s prow, and invited the townsmen to come and fasten their teeth in it, which many did with savage satisfaction.

The Duke of Alba ruthlessly attempted to suppress the Protestant movement in the Netherlands. Netherlanders were “burned, strangled, beheaded, or buried alive” by his “Blood Council” and his Spanish soldiers. Severed heads and decapitated corpses were displayed along streets and roads to terrorise the population into submission. Alba boasted of having executed 18,600,[68][69] but this figure does not include those who perished by war and famine.[citation needed]

The first great siege was Alba’s effort to capture Haarlem and thereby cut Holland in half. It dragged on from December 1572 to the next summer, when Haarlemers finally surrendered on 13 July upon the promise that the city would be spared from being sacked. It was a stipulation Don Fadrique was unable to honour, when his soldiers mutinied, angered over pay owed and the miserable conditions they endured during the long, cold months of the campaign.[70] On 4 November 1576, Spanish tercios seized Antwerp and subjected it to the worst pillage in the Netherlands’ history. The citizens resisted but were overcome; seven thousand of them were killed; a thousand buildings were torched; men, women, and children were slaughtered by soldiers, who invoked the name of Spain’s patron saint, ¡Santiago! ¡España! ¡A sangre, a carne, a fuego, a sacco! (Saint James! Spain! To blood, to the flesh, to fire, to sack!)[71]

Following the sack of Antwerp, delegates from Catholic Brabant, Protestant Holland and Zeeland agreed, at Ghent, to join Utrecht and William the Silent in driving out all Spanish troops and forming a new government for the Netherlands. Don Juan of Austria, the new Spanish governor, was forced to concede initially, but within months returned to active hostilities. As the fighting restarted, the Dutch began to look for help from the Protestant Elizabeth I of England, but she initially stood by her commitments to the Spanish in the Treaty of Bristol of 1574. The result was that when the next large-scale battle did occur at Gembloux in 1578, the Spanish forces easily won the day, killing at least 10,000 rebels, with the Spanish suffering few losses.[72][dubious ] In light of the defeat at Gembloux, the southern states of the Seventeen Provinces (today in northern France and Belgium) distanced themselves from the rebels in the north with the 1579 Union of Arras, which expressed their loyalty to Philip II of Spain. Opposing them, the northern half of the Seventeen Provinces forged the Union of Utrecht (also of 1579) in which they committed to support each other in their defence against the Spanish army.[73] The Union of Utrecht is seen as the foundation of the modern Netherlands.[citation needed]

Spanish troops sacked Maastricht in 1579, killing over 10,000 civilians and thereby ensuring the rebellion continued.[74] In 1581, the northern provinces adopted the Act of Abjuration, the declaration of independence in which the provinces officially deposed Philip II as reigning monarch in the northern provinces.[75] Against the rebels Philip could draw on the resources of the Spanish Empire, including in Iberia, Spanish America, Spanish Italy, and the Spanish Netherlands. Queen Elizabeth I of England sympathised with the Dutch struggle against England’s Spanish rival and sent an army of 7,600 soldiers to aid the Dutch in their war with the Catholic Spanish.[76] English forces under the Earl of Leicester and then Lord Willoughby faced the Spanish in the Netherlands under the Duke of Parma in a series of largely indecisive actions that tied down significant numbers of Spanish troops and bought time for the Dutch to reorganise their defences.[77] The war continued until 1648, when Spain under King Philip IV finally recognised the independence of the seven north-western provinces in the Peace of Münster. Parts of the southern provinces became de facto colonies of the new republican-mercantile empire.[citation needed]

Dutch Republic (1581–1795)

After declaring their independence, the provinces of Holland, Zeeland, Groningen, Friesland, Utrecht, Overijssel, and Gelderland formed a confederation. All these duchies, lordships and counties were autonomous and had their own government, the States-Provincial. The States General, the confederal government, were seated in The Hague and consisted of representatives from each of the seven provinces. The sparsely populated region of Drenthe was part of the republic too, although it was not considered one of the provinces. Moreover, the Republic had come to occupy during the Eighty Years’ War a number of so-called Generality Lands in Flanders, Brabant and Limburg. Their population was mainly Roman Catholic, and these areas did not have a governmental structure of their own and were used as a buffer zone between the Republic and the Spanish-controlled Southern Netherlands.[78]

In the Dutch Golden Age, spanning much of the 17th century, the Dutch Empire grew to become one of the major seafaring and economic powers, alongside Portugal, Spain, France and England. Science, military and art (especially painting) were among the most acclaimed in the world. By 1650, the Dutch owned 16,000 merchant ships.[79] The Dutch East India Company and the Dutch West India Company established colonies and trading posts all over the world, including ruling the western parts of Taiwan between 1624–1662 and 1664–1667. The Dutch settlement in North America began with the founding of New Amsterdam on the southern part of Manhattan in 1614. In South Africa, the Dutch settled the Cape Colony in 1652. Dutch colonies in South America were established along the many rivers in the fertile Guyana plains, among them Colony of Surinam (now Suriname). In Asia, the Dutch established the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia), and the only western trading post in Japan, Dejima.[citation needed]

During the period of Proto-industrialisation, the empire received 50% of textiles and 80% of silks import from the India’s Mughal Empire, chiefly from its most developed region known as Bengal Subah.[80][81][82][83]

Many economic historians regard the Netherlands as the first thoroughly capitalist country in the world. In early modern Europe, it had the wealthiest trading city (Amsterdam) and the first full-time stock exchange. The inventiveness of the traders led to insurance and retirement funds as well as phenomena such as the boom-bust cycle, the world’s first asset-inflation bubble, the tulip mania of 1636–1637, and the world’s first bear raider, Isaac le Maire, who forced prices down by dumping stock and then buying it back at a discount.[84] In 1672 – known in Dutch history as the Rampjaar (Disaster Year) – the Dutch Republic was at war with France, England and three German Bishoprics simultaneously. At sea, it could successfully prevent the English and French navies from entering the western shores. On land, however, it was almost taken over internally by the advancing French and German armies coming from the east. It managed to turn the tide by inundating parts of Holland but could never recover to its former glory again and went into a state of a general decline in the 18th century, with economic competition from England and long-standing rivalries between the two main factions in Dutch society, the republican Staatsgezinden and the supporters of the stadtholder the Prinsgezinden as main political factions.[85]

Batavian Republic and Kingdom (1795–1890)

With the armed support of revolutionary France, Dutch republicans proclaimed the Batavian Republic, modelled after the French Republic and rendering the Netherlands a unitary state on 19 January 1795. The stadtholder William V of Orange had fled to England. But from 1806 to 1810, the Kingdom of Holland was set up by Napoleon Bonaparte as a puppet kingdom governed by his brother Louis Bonaparte to control the Netherlands more effectively. However, King Louis Bonaparte tried to serve Dutch interests instead of his brother’s, and he was forced to abdicate on 1 July 1810. The Emperor sent in an army and the Netherlands became part of the French Empire until the autumn of 1813 when Napoleon was defeated in the Battle of Leipzig.[citation needed]

William Frederick, son of the last stadtholder, returned to the Netherlands in 1813 and proclaimed himself Sovereign Prince of the Netherlands. Two years later, the Congress of Vienna added the southern Netherlands to the north to create a strong country on the northern border of France. William Frederick raised this United Netherlands to the status of a kingdom and proclaimed himself as King William I in 1815.[citation needed] In addition, William became hereditary Grand Duke of Luxembourg in exchange for his German possessions. However, the Southern Netherlands had been culturally separate from the north since 1581, and rebelled. The south gained independence in 1830 as Belgium (recognised by the Northern Netherlands in 1839 as the Kingdom of the Netherlands was created by decree), while the personal union between Luxembourg and the Netherlands was severed in 1890, when William III died with no surviving male heirs. Ascendancy laws prevented his daughter Queen Wilhelmina from becoming the next Grand Duchess.[citation needed]

The Belgian Revolution at home and the Java War in the Dutch East Indies brought the Netherlands to the brink of bankruptcy. However, the Cultivation System was introduced in 1830; in the Dutch East Indies, 20% of village land had to be devoted to government crops for export. The policy brought the Dutch enormous wealth and made the colony self-sufficient.[citation needed]

The Netherlands abolished slavery in its colonies in 1863.[86] Enslaved people in Suriname would be fully free only in 1873, since the law stipulated that there was to be a mandatory 10-year transition.[87]

World wars and beyond (1890–present)

The Netherlands was able to remain neutral during World War I, in part because the import of goods through the Netherlands proved essential to German survival until the blockade by the British Royal Navy in 1916.[88] That changed in World War II, when Nazi Germany invaded the Netherlands on 10 May 1940. The Rotterdam Blitz forced the main element of the Dutch army to surrender four days later. During the occupation, over 100,000 Dutch Jews[89] were rounded up and transported to Nazi extermination camps; only a few of them survived. Dutch workers were conscripted for forced labour in Germany, civilians who resisted were killed in reprisal for attacks on German soldiers, and the countryside was plundered for food. Although there were thousands of Dutch who risked their lives by hiding Jews from the Germans, over 20,000 Dutch fascists joined the Waffen SS,[90] fighting on the Eastern Front.[91] Political collaborators were members of the fascist NSB, the only legal political party in the occupied Netherlands. On 8 December 1941, the Dutch government-in-exile in London declared war on Japan,[92] but could not prevent the Japanese occupation of the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia).[93] In 1944–45, the First Canadian Army, which included Canadian, British and Polish troops, was responsible for liberating much of the Netherlands.[94] Soon after VE Day, the Dutch fought a colonial war against the new Republic of Indonesia.[citation needed]

In 1954, the Charter for the Kingdom of the Netherlands reformed the political structure of the Netherlands, which was a result of international pressure to carry out decolonisation. The Dutch colonies of Surinam and Curaçao and Dependencies and the European country all became countries within the Kingdom, on a basis of equality. Indonesia had declared its independence in August 1945 (recognised in 1949), and thus was never part of the reformed Kingdom.[citation needed] Suriname followed in 1975. After the war, the Netherlands left behind an era of neutrality and gained closer ties with neighbouring states. The Netherlands was one of the founding members of Benelux and NATO.[95][96] In the 1950’s, the Netherlands became one of the six founding countries of the European Communities, following the 1952 establishment of the European Coal and Steel Community, and subsequent 1958 creations of the European Economic Community and European Atomic Energy Community.[97] In 1993, the former two of these were incorporated into the European Union.[97]

Government-encouraged emigration efforts to reduce population density prompted some 500,000 Dutch people to leave the country after the war.[98] The 1960s and 1970s were a time of great social and cultural change, such as rapid de-pillarisation characterised by the decay of the old divisions along political and religious lines. Students and other youth rejected traditional mores and pushed for change in matters such as women’s rights, sexuality, disarmament and environmental issues. In 2002 the euro was introduced as fiat money, and in 2010 the Netherlands Antilles was dissolved. Referendums were held on each island to determine their future status. As a result, the islands of Bonaire, Sint Eustatius and Saba (the BES islands) were to obtain closer ties with the Netherlands. This led to the incorporation of these three islands into the country of the Netherlands as special municipalities upon the dissolution of the Netherlands Antilles. The special municipalities are collectively known as the Caribbean Netherlands.[citation needed]

In recent times, much of the Netherlands has seen a reclamation of land from what were once waterways.[citation needed]

Geography

According to the Central Bureau of Statistics, the European Netherlands has a total area of 41,543 km2 (16,040 sq mi), including water bodies; and a land area of 33,481 km2 (12,927 sq mi). The Caribbean Netherlands has a total area of 328 km2 (127 sq mi)[99] It lies between latitudes 50° and 54° N, and longitudes 3° and 8° E.[citation needed]

The Netherlands is geographically very low relative to sea level and is considered a flat country, with about 26% of its area and 21% of its population[100] located below sea level, and only about 50% of its land exceeding one metre above sea level.[citation needed] The European part of the country is for the most part flat, with the exception of foothills in the far southeast, up to a height of no more than 321 metres, and some low hill ranges in the central parts. Most of the areas below sea level are caused by peat extraction or achieved through land reclamation. Since the late 16th century, large polder areas are preserved through elaborate drainage systems that include dikes, canals and pumping stations. Nearly 17% of the country’s land area is reclaimed from the sea and from lakes.[citation needed]

Much of the country was originally formed by the estuaries of three large European rivers: the Rhine (Rijn), the Meuse (Maas) and the Scheldt (Schelde), as well as their tributaries. The south-western part of the Netherlands is to this day a river delta of these three rivers, the Rhine-Meuse-Scheldt delta.[citation needed]

The European Netherlands is divided into north and south parts by the Rhine, the Waal, its main tributary branch, and the Meuse. In the past, these rivers functioned as a natural barrier between fiefdoms and hence historically created a cultural divide, as is evident in some phonetic traits that are recognisable on either side of what the Dutch call their “Great Rivers” (de Grote Rivieren). Another significant branch of the Rhine, the IJssel river, discharges into Lake IJssel, the former Zuiderzee (‘southern sea’). Just like the previous, this river forms a linguistic divide: people to the northeast of this river speak Dutch Low Saxon dialects (except for the province of Friesland, which has its own language).[101]

Geology

The modern Netherlands formed as a result of the interplay of the four main rivers (Rhine, Meuse, Schelde and IJssel) and the influence of the North Sea. The Netherlands is mostly composed of deltaic, coastal and eolian derived sediments during the Pleistocene glacial and interglacial periods.[citation needed]

Almost the entire west Netherlands is composed of the Rhine–Meuse river estuary, but human intervention greatly modified the natural processes at work. Most of the western Netherlands is below sea level due to the human process of turning standing bodies of water into usable land, a polder.[citation needed]

In the east of the Netherlands, remains are found of the last ice age, which ended approximately ten thousand years ago. As the continental ice sheet moved in from the north, it pushed moraine forward. The ice sheet halted as it covered the eastern half of the Netherlands. After the ice age ended, the moraine remained in the form of a long hill-line. The cities of Arnhem and Nijmegen are built upon these hills.[102]

Floods

Over the centuries, the Dutch coastline has changed considerably as a result of natural disasters and human intervention.

On 14 December 1287, St. Lucia’s flood affected the Netherlands and Germany, killing more than 50,000 people in one of the most destructive floods in recorded history.[103] The St. Elizabeth flood of 1421 and the mismanagement in its aftermath destroyed a newly reclaimed polder, replacing it with the 72 km2 (28 sq mi) Biesbosch tidal floodplains in the south-centre. The huge North Sea flood of early February 1953 caused the collapse of several dikes in the south-west of the Netherlands; more than 1,800 people drowned in the flood. The Dutch government subsequently instituted a large-scale programme, the “Delta Works“, to protect the country against future flooding, which was completed over a period of more than thirty years.[citation needed]

The impact of disasters was, to an extent, increased through human activity. Relatively high-lying swampland was drained to be used as farmland. The drainage caused the fertile peat to contract and ground levels to drop, upon which groundwater levels were lowered to compensate for the drop in ground level, causing the underlying peat to contract further. Additionally, until the 19th-century peat was mined, dried, and used for fuel, further exacerbating the problem. Centuries of extensive and poorly controlled peat extraction lowered an already low land surface by several metres. Even in flooded areas, peat extraction continued through turf dredging.[citation needed]

Because of the flooding, farming was difficult, which encouraged foreign trade, the result of which was that the Dutch were involved in world affairs since the early 14th/15th century.[104]

To guard against floods, a series of defences against the water were contrived. In the first millennium AD, villages and farmhouses were built on hills called terps. Later, these terps were connected by dikes. In the 12th century, local government agencies called “waterschappen“ (“water boards”) or “hoogheemraadschappen“ (“high home councils”) started to appear, whose job it was to maintain the water level and to protect a region from floods; these agencies continue to exist. As the ground level dropped, the dikes by necessity grew and merged into an integrated system. By the 13th century windmills had come into use to pump water out of areas below sea level. The windmills were later used to drain lakes, creating the famous polders.[105]

In 1932 the Afsluitdijk (“Closure Dike”) was completed, blocking the former Zuiderzee (Southern Sea) from the North Sea and thus creating the IJsselmeer (IJssel Lake). It became part of the larger Zuiderzee Works in which four polders totalling 2,500 square kilometres (965 sq mi) were reclaimed from the sea.[106][107]

The Netherlands is one of the countries that may suffer most from climate change. Not only is the rising sea a problem, but erratic weather patterns may cause the rivers to overflow.[108][109][110]

Delta Works

After the 1953 disaster, the Delta Works was constructed, which is a comprehensive set of civil works throughout the Dutch coast. The project started in 1958 and was largely completed in 1997 with the completion of the Maeslantkering. Since then, new projects have been periodically started to renovate and renew the Delta Works. The main goal of the Delta project was to reduce the risk of flooding in South Holland and Zeeland to once per 10,000 years (compared to once per 4000 years for the rest of the country). This was achieved by raising 3,000 km (1,900 mi) of outer sea-dikes and 10,000 km (6,200 mi) of the inner, canal, and river dikes, and by closing off the sea estuaries of the Zeeland province. New risk assessments occasionally show problems requiring additional Delta project dike reinforcements. The Delta project is considered by the American Society of Civil Engineers as one of the seven wonders of the modern world.[111]

It is anticipated that global warming in the 21st century will result in a rise in sea level. The Netherlands is actively preparing for a sea-level rise. A politically neutral Delta Commission has formulated an action plan to cope with a sea-level rise of 1.10 m (4 ft) and a simultaneous land height decline of 10 cm (4 in). The plan encompasses the reinforcement of the existing coastal defences like dikes and dunes with 1.30 m (4.3 ft) of additional flood protection. Climate change will not only threaten the Netherlands from the seaside but could also alter rainfall patterns and river run-off. To protect the country from river flooding, another programme is already being executed. The Room for the River plan grants more flow space to rivers, protects the major populated areas and allows for periodic flooding of indefensible lands. The few residents who lived in these so-called “overflow areas” have been moved to higher ground, with some of that ground having been raised above anticipated flood levels.[112]

Climate change

Nature

The Netherlands has 20 national parks and hundreds of other nature reserves, that include lakes, heathland, woods, dunes, and other habitats. Most of these are owned by Staatsbosbeheer, the national department for forestry and nature conservation and Natuurmonumenten (literally ‘Natures monuments’), a private organisation that buys, protects and manages nature reserves. The Dutch part of the Wadden Sea in the north, with its tidal flats and wetlands, is rich in biological diversity, and was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Nature Site in 2009.[citation needed]

The Oosterschelde, formerly the northeast estuary of the river Scheldt was designated a national park in 2002, thereby making it the largest national park in the Netherlands at an area of 370 km2 (140 sq mi). It consists primarily of the salt waters of the Oosterschelde but also includes mudflats, meadows, and shoals. Because of the large variety of sea life, including unique regional species, the park is popular with Scuba divers. Other activities include sailing, fishing, cycling, and bird watching.[citation needed]

Phytogeographically, the European Netherlands is shared between the Atlantic European and Central European provinces of the Circumboreal Region within the Boreal Kingdom. According to the World Wide Fund for Nature, the European territory of the Netherlands belongs to the ecoregion of Atlantic mixed forests.[118] In 1871, the last old original natural woods were cut down,[119] and most woods today are planted monocultures of trees like Scots pine and trees that are not native to the Netherlands.[citation needed] These woods were planted on anthropogenic heaths and sand-drifts (overgrazed heaths) (Veluwe). The Netherlands had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 0.6/10, ranking it 169th globally out of 172 countries.[120]

The number of flying insects in the Netherlands has dropped by 75% since the 1990s.[121]

Caribbean islands

In the Lesser Antilles islands of the Caribbean, the territories of Curaçao, Aruba and Sint Maarten have a constituent country status within the wider Kingdom of the Netherlands. Another three territories which make up the Caribbean Netherlands are designated as special municipalities of the Netherlands. The Caribbean Netherlands have maritime borders with Anguilla, Curaçao, France (Saint Barthélemy), Saint Kitts and Nevis, Sint Maarten, the U.S. Virgin Islands and Venezuela.[122]

Within this island group:

The islands of the Caribbean Netherlands enjoy a tropical climate with warm weather all year round. The Leeward Antilles are warmer and drier than the Windward islands. In summer, the Windward Islands can be subject to hurricanes.[citation needed]

Government and politics

The Netherlands has been a constitutional monarchy since 1815, and due to the efforts of Johan Rudolph Thorbecke[123] became a parliamentary democracy in 1848. The Netherlands is described as a consociational state. Dutch politics and governance are characterised by an effort to achieve broad consensus on important issues, within both the political community and society as a whole. In 2017, The Economist ranked the Netherlands as the 11th most democratic country in the world.[citation needed]

The monarch is the head of state, at present King Willem-Alexander of the Netherlands. Constitutionally, the position is equipped with limited powers. By law, the King has the right to be periodically briefed and consulted on government affairs. Depending on the personalities and relationships of the King and the ministers, the monarch might have influence beyond the power granted by the Constitution of the Netherlands.[citation needed]

The executive power is formed by the Council of Ministers, the deliberative organ of the Dutch cabinet. The cabinet usually consists of 13 to 16 ministers and a varying number of state secretaries. One to three ministers are ministers without portfolio. The head of government is the Prime Minister of the Netherlands, who often is the leader of the largest party of the coalition. The Prime Minister is a primus inter pares, with no explicit powers beyond those of the other ministers. Mark Rutte has been Prime Minister since October 2010; the Prime Minister had been the leader of the largest party of the governing coalition continuously since 1973.[citation needed]

The cabinet is responsible to the bicameral parliament, the States General, which also has legislative powers. The 150 members of the House of Representatives, the lower house, are elected in direct elections on the basis of party-list proportional representation. These are held every four years, or sooner in case the cabinet falls (for example: when one of the chambers carries a motion of no confidence, the cabinet offers its resignation to the monarch). The provincial assemblies, the States-Provincial, are directly elected every four years as well. The members of the provincial assemblies elect the 75 members of the Senate, the upper house, which has the power to reject laws, but not propose or amend them. Both houses send members to the Benelux Parliament, a consultative council.[citation needed]

Political culture

Both trade unions and employers organisations are consulted beforehand in policymaking in the financial, economic and social areas. They meet regularly with the government in the Social-Economic Council. This body advises government and its advice cannot be put aside easily.[citation needed]

The Netherlands has a tradition of social tolerance.[124] In the 18th century, while the Dutch Reformed Church was the state religion, Catholicism, other forms of Protestantism, such as Baptists and Lutherans, as well as Judaism were tolerated but discriminated against.[125]

In the late 19th century this Dutch tradition of religious tolerance transformed into a system of pillarisation, in which religious groups coexisted separately and only interacted at the level of government.[126] This tradition of tolerance influences Dutch criminal justice policies on recreational drugs, prostitution, LGBT rights, euthanasia, and abortion, which are among the most liberal in the world.[citation needed]

Political parties

No single party has held a majority in parliament since the 19th century, and as a result, coalition cabinets had to be formed. Since suffrage became universal in 1917, the Dutch political system has been dominated by three families of political parties: Christian Democrats (currently the CDA), Social Democrats (currently the PvdA), and Liberals (currently the VVD).

These parties co-operated in coalition cabinets in which the Christian Democrats had always been a partner: so either a centre-left coalition of the Christian Democrats and Social Democrats was ruling or a centre-right coalition of Christian Democrats and Liberals. In the 1970s, the party system became more volatile: the Christian Democratic parties lost seats, while new parties became successful, such as the radical democrat and progressive liberal Democrats 66 (D66) or the ecologist party GroenLinks (GL).[citation needed]

In the 1994 election, the CDA lost its dominant position. A “purple” cabinet was formed by the VVD, D66, and PvdA. In the 2002 elections, this cabinet lost its majority, because of an increased support for the CDA and the rise of the right-wing LPF, a new political party, around Pim Fortuyn, who was assassinated a week before the elections. A short-lived cabinet was formed by CDA, VVD, and LPF, which was led by the CDA Leader Jan Peter Balkenende. After the 2003 elections, in which the LPF lost most of its seats, a cabinet was formed by the CDA, VVD, and D66. The cabinet initiated an ambitious programme of reforming the welfare state, the healthcare system, and immigration policy.[citation needed]

In June 2006, the cabinet fell after D66 voted in favour of a motion of no confidence against the Minister of Immigration and Integration, Rita Verdonk, who had instigated an investigation of the asylum procedure of Ayaan Hirsi Ali, a VVD MP. A caretaker cabinet was formed by the CDA and VVD, and general elections were held on 22 November 2006. In these elections, the CDA remained the largest party and the Socialist Party made the largest gains. The formation of a new cabinet took three months, resulting in a coalition of CDA, PvdA, and Christian Union.[citation needed]

On 20 February 2010, the cabinet fell when the PvdA refused to prolong the involvement of the Dutch Army in Uruzgan, Afghanistan.[127] Snap elections were held on 9 June 2010, with devastating results for the previously largest party, the CDA, which lost about half of its seats, resulting in 21 seats. The VVD became the largest party with 31 seats, closely followed by the PvdA with 30 seats. The big winner of the 2010 elections was Geert Wilders, whose right wing PVV,[128][129] the ideological successor to the LPF, more than doubled its number of seats.[130] Negotiation talks for a new government resulted in a minority government, led by VVD (a first) in coalition with CDA, which was sworn in on 14 October 2010. This unprecedented minority government was supported by PVV, but proved ultimately to be unstable,[131] when on 21 April 2012, Wilders, leader of PVV, unexpectedly ‘torpedoed seven weeks of austerity talks’ on new austerity measures, paving the way for early elections.[132][133][134]

VVD and PvdA won a majority in the House of Representatives during the 2012 general election. On 5 November 2012 they formed the second Rutte cabinet. After the 2017 general election, VVD, Christian Democratic Appeal, Democrats 66 and ChristenUnie formed the third Rutte cabinet. This cabinet resigned in January 2021, two months before the general election, after a child welfare fraud scandal.[135] In March 2021, centre-right VVD of Prime Minister Mark Rutte was the winner of the elections, securing 34 out of 150 seats. The second biggest party was the centre-left D66 with 24 seats. Geert Wilders‘ far-right party lost support. Prime Minister Mark Rutte, in power since 2010, formed his fourth coalition government, the Fourth Rutte cabinet, consisting of the same parties as the previous one.[136]

Government

Administrative divisions

The Netherlands is divided into twelve provinces, each under a King’s Commissioner (Commissaris van de Koning). Informally in Limburg province this position is named Governor (Gouverneur). All provinces are divided into municipalities (gemeenten), of which there are 344 (2022).[137][138]

The country is also subdivided into 21 water districts, governed by a water board (waterschap or hoogheemraadschap), each having authority in matters concerning water management.[139][140] The creation of water boards actually pre-dates that of the nation itself, the first appearing in 1196. The Dutch water boards are among the oldest democratic entities in the world still in existence. Direct elections of the water boards take place every four years.

The administrative structure on the three BES islands, collectively known as the Caribbean Netherlands, is outside the twelve provinces. These islands have the status of openbare lichamen (public bodies).[141] In the Netherlands these administrative units are often referred to as special municipalities.

Within the Dutch town of Baarle-Nassau, are 22 Belgian exclaves[142] and within those are 8 Dutch enclaves.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Foreign relations

The history of Dutch foreign policy has been characterised by its neutrality. Since World War II, the Netherlands has become a member of a large number of international organisations, most prominently the UN, NATO and the EU. The Dutch economy is very open and relies strongly on international trade.[citation needed]

The foreign policy of the Netherlands is based on four basic commitments: to Atlantic co-operation, to European integration, to international development and to international law. One of the more controversial international issues surrounding the Netherlands is its liberal policy towards soft drugs.[citation needed]

During and after the Dutch Golden Age, the Dutch people built up a commercial and colonial empire. The most important colonies were present-day Suriname and Indonesia. Indonesia became independent after the Indonesian National Revolution in the 1940s following a war of independence, international pressure and several United Nations Security Council resolutions. Suriname became independent in 1975. The historical ties inherited from its colonial past still influence the foreign relations of the Netherlands. In addition, many people from these countries are living permanently in the Netherlands.[citation needed]

Military

The Netherlands has one of the oldest standing armies in Europe; it was first established as such by Maurice of Nassau in the late 1500s. The Dutch army was used throughout the Dutch Empire. After the defeat of Napoleon, the Dutch army was transformed into a conscription army. The army was unsuccessfully deployed during the Belgian Revolution in 1830. After 1830, it was deployed mainly in the Dutch colonies, as the Netherlands remained neutral in European wars (including the First World War), until the Netherlands was invaded in World War II and defeated by the Wehrmacht in May 1940.[citation needed]

The Netherlands abandoned its neutrality in 1948 when it signed the Treaty of Brussels, and became a founding member of NATO in 1949. The Dutch military was therefore part of the NATO strength in Cold War Europe, deploying its army to several bases in Germany. More than 3,000 Dutch soldiers were assigned to the 2nd Infantry Division of the United States Army during the Korean War. In 1996 conscription was suspended, and the Dutch army was once again transformed into a professional army. Since the 1990s the Dutch army has been involved in the Bosnian War and the Kosovo War, it held a province in Iraq after the defeat of Saddam Hussein, and it was engaged in Afghanistan.[citation needed]

The military is composed of four branches, all of which carry the prefix Koninklijke (Royal):

The submarine service opened to women on 1 January 2017. The Korps Commandotroepen, the Special Operations Force of the Netherlands Army, is open to women, but because of the extremely high physical demands for initial training, it is almost impossible for a woman to become a commando.[146] The Dutch Ministry of Defence employs more than 70,000 personnel, including over 20,000 civilians and over 50,000 military personnel.[147] In April 2011 the government announced a major reduction in its military because of a cut in government expenditure, including a decrease in the number of tanks, fighter aircraft, naval ships and senior officials.[148]

The Netherlands has ratified many international conventions concerning war law. The Netherlands decided not to sign the UN treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.[149]

Economy

The Netherlands has a developed economy and has been playing a special role in the European economy for many centuries. Since the 16th century, shipping, fishing, agriculture, trade, and banking have been leading sectors of the Dutch economy. The Netherlands has a high level of economic freedom. The Netherlands is one of the top countries in the Global Enabling Trade Report (2nd in 2016), and was ranked the fifth most competitive economy in the world by the Swiss International Institute for Management Development in 2017.[150] In addition, the country was ranked the 5th most innovative nation in the world in the 2022 Global Innovation Index down from 2nd in 2018.[151][152]

As of 2020[update], the key trading partners of the Netherlands were Germany, Belgium, the United Kingdom, the United States, France, Italy, China and Russia.[153] The Netherlands is one of the world’s 10 leading exporting countries. Foodstuffs form the largest industrial sector. Other major industries include chemicals, metallurgy, machinery, electrical goods, trade, services and tourism. Examples of international Dutch companies operating in Netherlands include Randstad, Unilever, Heineken, KLM, financial services (ING, ABN AMRO, Rabobank), chemicals (DSM, AKZO), petroleum refining (Royal Dutch Shell), electronic machinery (Philips, ASML), and satellite navigation (TomTom).

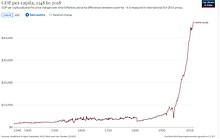

The Netherlands has the 17th-largest economy in the world, and ranks 11th in GDP (nominal) per capita. Between 1997 and 2000 annual economic growth (GDP) averaged nearly 4%, well above the European average. Growth slowed considerably from 2001 to 2005 with the global economic slowdown, but accelerated to 4.1% in the third quarter of 2007. In May 2013, inflation was at 2.8% per year.[154] In April 2013, unemployment was at 8.2% (or 6.7% following the ILO definition) of the labour force.[155] In February 2019, this was reduced to 3.4%.[156]

In Q3 and Q4 2011, the Dutch economy contracted by 0.4% and 0.7%, respectively, because of European Debt Crisis, while in Q4 the Eurozone economy shrunk by 0.3%.[157] The Netherlands also has a relatively low GINI coefficient of 0.326. Despite ranking 11th in GDP per capita, UNICEF ranked the Netherlands 1st in child well-being in rich countries, both in 2007 and in 2013.[158][159][160] On the Index of Economic Freedom Netherlands is the 14th most free market capitalist economy out of 180 surveyed countries.

Amsterdam is the financial and business capital of the Netherlands.[161] The Amsterdam Stock Exchange (AEX), part of Euronext, is the world’s oldest stock exchange and is one of Europe’s largest bourses. It is situated near Dam Square in the city’s centre. As a founding member of the euro, the Netherlands replaced (for accounting purposes) its former currency, the “gulden” (guilder), on 1 January 1999, along with 15 other adopters of the euro. Actual euro coins and banknotes followed on 1 January 2002. One euro was equivalent to 2.20371 Dutch guilders. In the Caribbean Netherlands, the United States dollar is used instead of the euro.[citation needed]

The Dutch location gives it prime access to markets in the UK and Germany, with the Port of Rotterdam being the largest port in Europe. Other important parts of the economy are international trade (Dutch colonialism started with co-operative private enterprises such as the Dutch East India Company), banking and transport. The Netherlands successfully addressed the issue of public finances and stagnating job growth long before its European partners. Amsterdam is the 5th-busiest tourist destination in Europe with more than 4.2 million international visitors.[162] Since the enlargement of the EU large numbers of migrant workers have arrived in the Netherlands from Central and Eastern Europe.[163]

The Netherlands continues to be one of the leading European nations for attracting foreign direct investment and is one of the five largest investors in the United States. The economy experienced a slowdown in 2005, but in 2006 recovered to the fastest pace in six years on the back of increased exports and strong investment. The pace of job growth reached 10-year highs in 2007. The Netherlands is the fourth-most competitive economy in the world, according to the World Economic Forum‘s Global Competitiveness Report.[164]

Natural gas

Beginning in the 1950s, the Netherlands discovered huge natural gas resources. The sale of natural gas generated enormous revenues for the Netherlands for decades, adding, over sixty years, hundreds of billions of euros to the government’s budget.[165] However, the unforeseen consequences of the country’s huge energy wealth impacted the competitiveness of other sectors of the economy, leading to the theory of Dutch disease.[165]

Apart from coal and gas, the country has no mining resources. The last coal mine was closed in 1974. The Groningen gas field, one of the largest natural-gas fields in the world, is situated near Slochteren. The exploitation of this field has resulted in €159 billion in accumulated revenue since the mid-1970s.[166] The field is operated by government-owned Gasunie and output is jointly exploited by the government, Royal Dutch Shell, and Exxon Mobil through NAM (Nederlandse Aardolie Maatschappij). “Gas extraction has resulted in increasingly strong earth tremors, some measuring as much as 3.6 on the Richter magnitude scale. The cost of damage repairs, structural improvements to buildings, and compensation for home value decreases has been estimated at €6.5 billion. Around 35,000 homes are said to be affected.”[167] The Netherlands has an estimated 25% of natural gas reserves in the EU.[168] The total energy sector accounted for almost 11% of the GDP in 2014.[169] Netherlands’ economy, mainly due to the large shares of natural gas reserves, is considered to have “very high” energy intensity rating.[170]

The Netherlands is faced with future challenges as the energy supply is forecasted to fall short of the demand by 2025 in the gas sector. This is attributed to the depletion of the Netherlands’ major gas field, Groningen, and the earthquakes that have hit the Groningen region.[171] In addition, there is ambiguity surrounding the feasibility of producing unconventional gas. The Netherlands relies heavily on natural gas to provide energy. Gas is the main source of heating for households in the Netherlands[168] and represented 35% of the energy mix in 2014.[172] Furthermore, The European Union 2020 package (20% reduction in GHG emissions, 20% renewables in the energy mix and 20% improvement in energy efficiency) enacted in 2009 has influenced the domestic energy politics of Netherlands and pressured non-state actors to give consent to more aggressive energy reforms that would reduce reliance on natural resources as a source of income to the economy.[173] Therefore, a transition towards renewable energy has been a key objective by Netherlands in order to safeguard the energy security of the country from natural resources depletion, mainly gas.[168] Netherlands has set a 14% renewable energy target of the total energy mix by 2020.[174] However, the continuation of providing tax breaks to electricity generated by coal and gas, and to the exploration and extraction of gas from fields that are “insufficiently” profitable,[175] renders a successful transition towards renewable energy more difficult to achieve due to inconsistencies in the policy mix. In 2011, it was estimated that the renewable energy sector received 31% (EUR 743MM), while the conventional energy sector received 69% (EUR 1.6B), of the total energy subsidies by the government.[175] Furthermore, the energy market in the Netherlands remains to be dominated by few major corporations Nuon, RWE, E.ON, Eneco, and Delta that have significant influence over the energy policy.[176] Renewable energy share in the energy mix is estimated to reach 12.4% by 2020, falling 1.6% short of the 14% target.[174][needs update]

Agriculture and natural resources

From a biological resource perspective, the Netherlands has a low endowment: the Netherlands’ biocapacity totals only 0.8 global hectares per person in 2016, 0.2 of which are dedicated to agriculture. The Dutch biocapacity per person is just about half of the 1.6 global hectares of biocapacity per person available worldwide.[178] In contrast, in 2016, the Dutch used on average 4.8 global hectares of biocapacity – their ecological footprint of consumption. This means the Dutch required nearly six times as much biocapacity as the Netherlands contains. As a result, the Netherlands was running a biocapacity deficit of 4.0 global hectares per person in 2016.

The Dutch agricultural sector is highly mechanised, and has a strong focus on international exports. It employs about 4% of the Dutch labour force but produces large surpluses in the food-processing industry and accounts for 21% of the Dutch total export value.[179] The Dutch rank first in the European Union and second worldwide in value of agricultural exports, behind only the United States,[180] with agricultural exports earning €80.7 billion in 2014,[181] up from €75.4 billion in 2012.[31] In 2019 agricultural exports were worth €94.5 billion.[182] In an effort to reduce agricultural pollution, the Dutch government is imposing strict limits on the productivity of the farming sector, triggering Dutch farmers’ protests, who fear for their livelihoods.[183]

One-third of the world’s exports of chilis, tomatoes, and cucumbers go through the country. The Netherlands also exports one-fifteenth of the world’s apples.[184]

A significant portion of Dutch agricultural exports consists of fresh-cut plants, flowers, and flower bulbs, with the Netherlands exporting two-thirds of the world’s total.[184]

Demographics

The Netherlands had an estimated population of 17,493,969 as of 30 April 2021.[144] It is the 5th most densely populated country in Europe, and except for Malta and very small city-states like Monaco, Vatican City and San Marino, it is the most densely populated country in Europe. And it is the 16th most densely populated country in the world with a density of 424 per square kilometre (1,100/sq mi). It is the 67th most populous country in the world. Between 1900 and 1950, the country’s population almost doubled from 5.1 to 10 million. From 1950 to 2000, the population further increased, to 15.9 million, though this represented a lower rate of population growth.[185] The estimated growth rate in 2013[update] is 0.44%.[186]

The fertility rate in the Netherlands is 1.78 children per woman (2018 estimate),[186] which is high compared with many other European countries, but below the rate of 2.1 children per woman required for natural population replacement, it remains considerably below the high of 5.39 children born per woman in 1879.[187] Netherlands subsequently has one of the oldest populations in the world, with the average age of 42.7 years.[186] Life expectancy is high in the Netherlands: 84.3 years for newborn girls and 79.7 for boys (2020 estimate).[186] The country has a migration rate of 1.9 migrants per 1,000 inhabitants per year.[186] The majority of the population of the Netherlands is ethnically Dutch. According to a 2005 estimate, the population was 80.9% Dutch, 2.4% Indonesian, 2.4% German, 2.2% Turkish, 2.0% Surinamese, 1.9% Moroccan, 0.8% Antillean and Aruban, and 7.4% others.[188] Some 150,000 to 200,000 people living in the Netherlands are expatriates, mostly concentrated in and around Amsterdam and The Hague, now constituting almost 10% of the population of these cities.[189][190]

The Dutch are the tallest people in the world, by nationality,[191] with an average height of 1.81 metres (5 ft 11.3 in) for adult males and 1.67 metres (5 ft 5.7 in) for adult females in 2009.[192] The average height of young males in the Netherlands increased from 5 feet, 4 inches to approximately 6 feet between the 1850s until the early 2000s.[193] People in the south are on average about 2 cm (0.8 inches) shorter than those in the north.[citation needed]

According to Eurostat, in 2010 there were 1.8 million foreign-born residents in the Netherlands, corresponding to 11.1% of the total population. Of these, 1.4 million (8.5%) were born outside the EU and 0.43 million (2.6%) were born in another EU Member State.[194] On 21 November 2016, there were 3.8 million residents in the Netherlands with at least one foreign-born parent (“migration background”).[195] On 1 January 2016, 26,2% of persons aged 0–50 had at least one parent born in a foreign country. 11,4% of persons aged 0–50 ‘of Dutch background’ belonged to the ‘third generation’. Of these 739,000 had western grandparents, 120,000 non-western. The third generation constitutes from persons born from two second generation immigrants or one second generation immigrant and one person with a Dutch background. First and second generation immigrants and the third generation were 34,5% of the population aged 0–50.[196] Over half the young people in Amsterdam and Rotterdam have a non-western background.[197] Dutch people, or descendants of Dutch people, are also found in migrant communities worldwide, notably in Canada, Australia, South Africa and the United States. According to the United States Census Bureau (2006), more than 5 million Americans claim total or partial Dutch ancestry.[198] There are close to 3 million Dutch-descended Afrikaners living in South Africa.[199] In 1940, there were 290,000 Europeans and Eurasians in Indonesia,[200] but most have since left the country.[201]

The Randstad is the country’s largest conurbation located in the west of the country and contains the four largest cities: Amsterdam in the province North Holland, Rotterdam and The Hague in the province South Holland, and Utrecht in the province Utrecht. The Randstad has a population of about 8.2 million inhabitants[202] and is the 5th largest metropolitan area in Europe. According to Dutch Central Statistics Bureau, in 2015, 28 per cent of the Dutch population had a spendable income above 45,000 euros (which does not include spending on health care or education).[203]

|

Largest municipalities in the Netherlands

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | ||

Amsterdam  Rotterdam |

1 | Amsterdam | North Holland | 905,234 | 11 | Apeldoorn | Gelderland | 165,648 |  The Hague  Utrecht |

| 2 | Rotterdam | South Holland | 656,050 | 12 | Arnhem | Gelderland | 164,096 | ||

| 3 | The Hague | South Holland | 552,995 | 13 | Haarlem | North Holland | 162,914 | ||

| 4 | Utrecht | Utrecht | 361,924 | 14 | Enschede | Overijssel | 160,383 | ||

| 5 | Eindhoven | North Brabant | 238,478 | 15 | Haarlemmermeer | North Holland | 159,346 | ||

| 6 | Groningen | Groningen | 234,649 | 16 | Amersfoort | Utrecht | 158,712 | ||

| 7 | Tilburg | North Brabant | 224,702 | 17 | Zaanstad | North Holland | 157,215 | ||

| 8 | Almere | Flevoland | 218,096 | 18 | ‘s-Hertogenbosch | North Brabant | 156,599 | ||

| 9 | Breda | North Brabant | 184,716 | 19 | Zwolle | Overijssel | 130,872 | ||

| 10 | Nijmegen | Gelderland | 179,073 | 20 | Zoetermeer | South Holland | 125,867 | ||

Functional urban areas

“Functional urban areas”[205] are a type of urban areas with large populations where commuters from nearby areas work in the core area. There are several functional urban areas officially identified in the Netherlands. The largest ones (with populations over 300,000) are listed below, which count the populations of the core city and their “commuting zones”.[206]

| Functional urban areas | Population (2015) |

|---|---|

| Amsterdam–Haarlem–Almere | 2,751,000 |

| Rotterdam–Dordrecht | 1,805,000 |

| The Hague–Delft | 1,052,000 |

| Utrecht | 875,000 |

| Eindhoven | 736,000 |

| Groningen | 474,000 |

| Arnhem | 420,000 |

| Enschede | 401,000 |

| Breda | 367,000 |

| Zwolle | 350,000 |

| Leiden | 339,000 |

| Nijmegen | 322,000 |

| Tilburg | 310,000 |

Language

The official language is Dutch, which is spoken by the vast majority of the inhabitants. The dialects most spoken in the Netherlands are the Brabantian–Hollandic dialects.[208]

Besides Dutch, West Frisian is recognised as a second official language in the northern province of Friesland (Fryslân in West Frisian).[209] West Frisian has a formal status for government correspondence in that province. In the European part of the kingdom two other regional languages are recognised under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages.[210]

The first of these recognised regional languages is Low Saxon (Nedersaksisch in Dutch). Low Saxon consists of several dialects of the Low German language spoken in the north and east of the Netherlands, like Tweants in the region of Twente, and Drents in the province of Drenthe.

Secondly, Limburgish is also recognised as a regional language. It consists of Dutch varieties of Meuse-Rhenish Franconian languages and is spoken in the south-eastern province of Limburg.[101] Ripuarian language, which is spoken in Kerkrade and Vaals in the form of, respectively, the Kerkrade dialect and the Vaals dialect[211][212] are legally treated as Limburgish as well – see Southeast Limburgish dialect.[citation needed]

English has a formal status in the special municipalities of Saba and Sint Eustatius. It is widely spoken on these islands. Papiamento has a formal status in the special municipality of Bonaire. Yiddish and the Romani language were recognised in 1996 as non-territorial languages.[213]